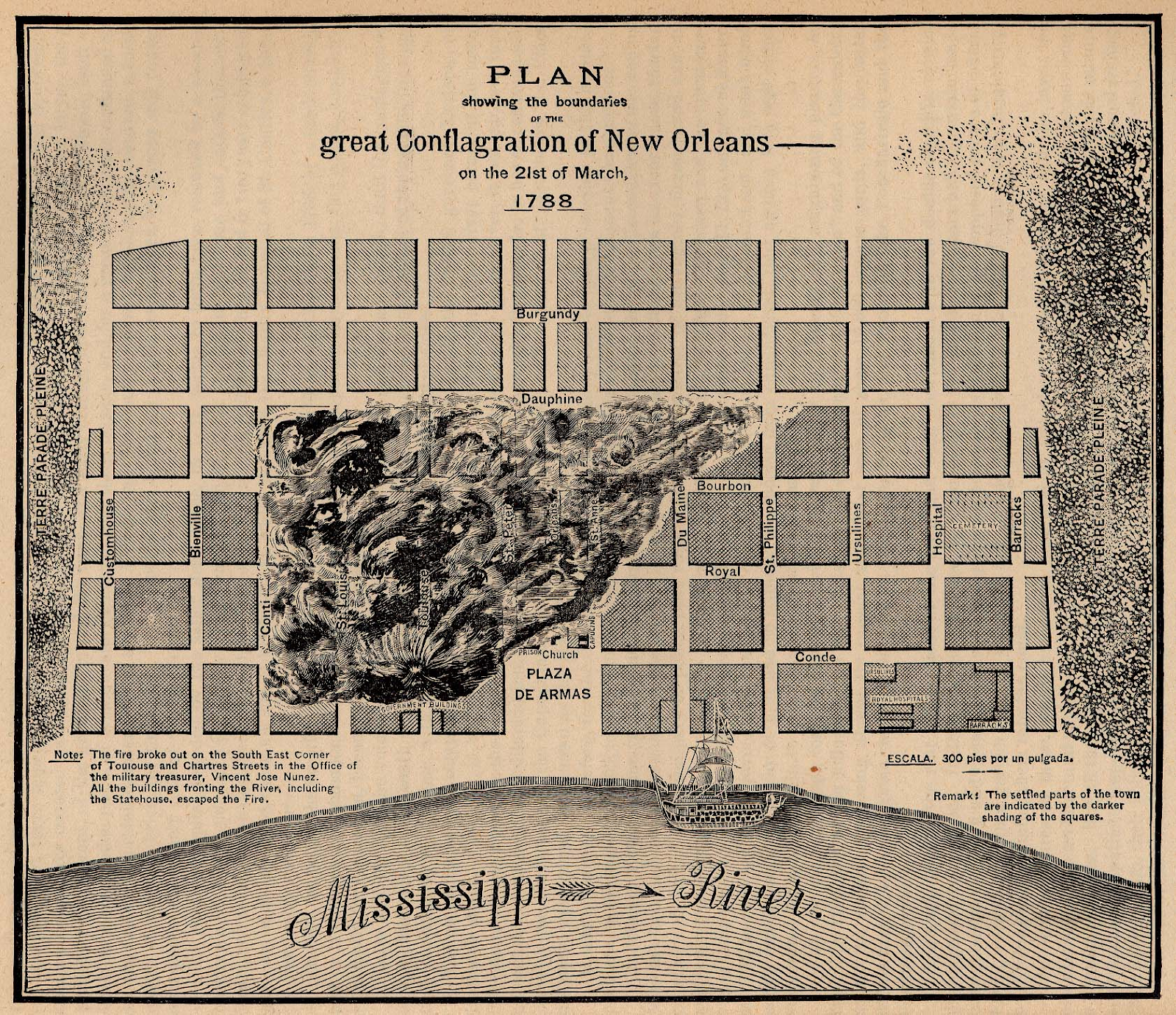

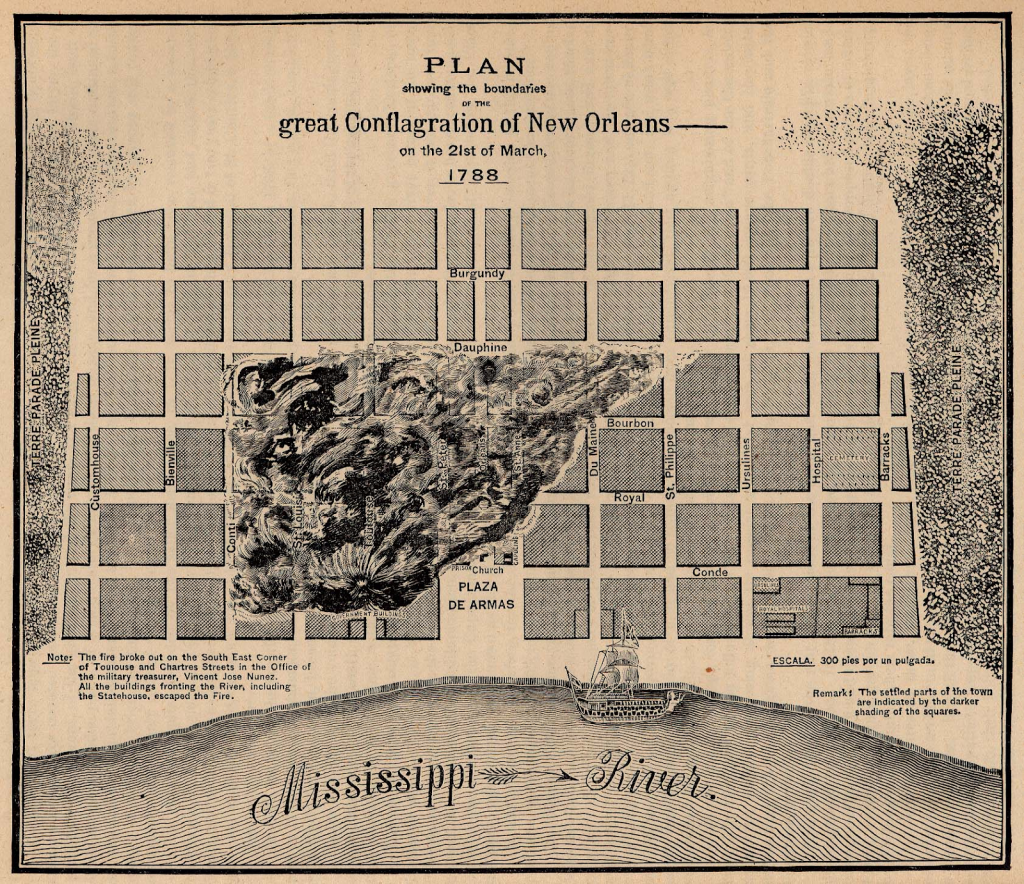

It seems no matter where they’re located in the world, every major city has suffered through a devastating fire. While some of the more famous blazes took place in Chicago and London, New Orleans has had several of its own. The largest of these took place in 1788, and the Great Conflagration of New Orleans might have been the end of the city if not for decisive leadership.

A Very Bad Good Friday

March 21st, 1788 was a very bad Good Friday for the City of New Orleans. Vicente Jose Nunez, the Spanish army’s paymaster, was a faithful man. A Catholic, he had a private altar in his home at the corner of Chartres and Toulouse streets. On this Good Friday, he’d lit up to 50 tall taper candles while praying. This act of piety was about to prove disastrous for, as he went out to attend to dinner, the unattended tapers caught fire to the drapes and, within minutes, had spread to the ceiling and wooden shingled roof. Strong southeasterly winds spread the flames through 18 blocks of tightly packed buildings, most made of cypress timbers.

Traditionally on Good Friday no church bells were rung. Even though doing so could have warned people of the growing fire, the priests refused to budge on the matter. This, combined with the fact that the city was woefully unprepared to stop such a blaze, led to 856 buildings being destroyed in just under five hours.

Perhaps the only saving grace of the Great Fire was that it occurred around 1:30 in the afternoon. Had it started at night, the loss of life would have been catastrophic. As it was, very few died and injuries were kept to a minimum since the citizens had the advantage of daylight to help them escape the burning buildings. Still, the loss of 4/5’s of the city, including every bakery, left people in despair of where they would live and how they would eat.

Better to Ask Forgiveness than Permission

Esteban Rodriguez Miro, the governor of Louisiana, looked out at his decimated capitol city. Families were wandering in shock, holding what few items or papers they’d been able to save from the blaze. He knew action must be immediately taken to secure them shelter and food. He ordered the army to provide tents to the people who could not be taken in by those who still had houses standing. A shipment of biscuits which had been bound for Natchez was instead distributed to the newly displaced and Miro himself stood outside of his home giving his own money to the most desperate of the poor.

In defiance of Spanish law which forbade the colony from trading with the newly formed United States or from allowing non-Spanish ships to enter the Gulf of Mexico, Governor Miro sent several ships to Philadelphia to secure flour and other vital supplies. He also sent letters to French holdings in the Caribbean for help. It was only after this that he wrote to King Charles III in Madrid asking the King to allow a French ship, The Trout, to supply New Orleans from nearby Saint Domingue. He also plead for clemency for the ships carrying the vital flour from Philadelphia and was successful in securing permission for both from the King.

Miro declared that all goods would remain the same prices as before the fire. In this way, he helped the colony avoid the heavy inflation that had crippled other cities’ recovery efforts after major disasters. He also sent out a call along the Mississippi for all farmers to send their goods to the city. This allowed New Orleans’ citizens to survive until the supplies from Philadelphia and Saint Domingue could arrive. Miro even, at the King’s expense, ordered barracks built close to the river to house the displaced as the army tents they were living in were a temporary solution at best.

Up from the Ashes

While his decisive action was enough to help the young colony survive the immediate aftermath of the fire, Miro knew that without changes to building codes and a fire suppression plan, the city would simply be primed for another blaze. Instead of allowing buildings to continue to be built with exposed cypress beams, they would now be built with brick or with timber encased in cement to prevent such a quick spreading of flames. The city also secured several new fire engines, leather buckets, and four pumps to help ensure such a fire would not happen again. And for the most part it worked. While fire did strike again in 1794, just over 200 buildings (mostly those which had not been built to the new code) were destroyed as opposed to the 856 lost in 1788.

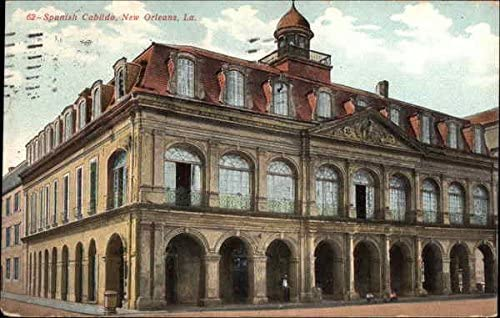

But the city was changed in other ways too. Miro’s success in gaining permission for New Orleans to trade with the United States and for foreign ships to enter the Gulf of Mexico allowed the city to become a major trading port. It also helped turn the colony from a struggling one into a hub of culture with grand Spanish architecture visitors to the city can still enjoy today.

So, the next time you wander through the French Quarter and see those beautiful wrought iron balconies on pastel-colored homes, say thanks to Governor Miro. Without his bold leadership, New Orleans would likely have remained nothing but ashes and rubble.