When the sun is shining, there’s hardly an image more iconic in New Orleans than that of a streetcar rumbling down St. Charles Avenue.

Tennesee Williams knew it when he wrote his 20th century masterpiece, A Streetcar Named Desire. By then, railway technology had already been spreading across the globe for a hundred years — the convergence of Industrial Revolution-era technological advancements like wrought-iron, grooved wheels and improved steam engines.

But these advancements weren’t only taking place oceans away. The first railroad track opened in the United States was in 1830, in Baltimore Harbor. Just a few short months later, way down south right here in New Orleans, our forebears were working on a train system of their own.

Humble Beginnings

It happened during a fantastic decade of growth for the city. In 1830, New Orleans’ population was 46,082. Just ten years later that number exploded to 102,193. As the population increased, residents spread outside the usual downtown neighborhoods.

The first local system to take them to those newly settled areas was the Pontchartrain Railroad and its legendary train, Smoky Mary.

The Daily Picayune reported “the axe was driven into the first tree” in March of 1830, as the Pontchartrain Railroad Company cleared land for the track. Within the year, rails were laid through marshes and over swamps, and — on April 23, 1831, as hundreds of curious onlookers gathered on the corner of Elysian Fields Avenue and Decatur Street — the first-ever rail trip west of the Allegheny Mountains took passengers the five miles north to the lakefront town of Milneburg.

But the trip didn’t go exactly as planned. The locomotives ordered from Great Britain hadn’t yet arrived, so the first 17 months of service were horse-drawn. It wasn’t until September of 1832 when the first steam-powered engine dragged 12 cars to Lake Pontchartrain. Still, New Orleans train travel was underway!

Historic

Just a year later, in 1833, serious local discussions began on the creation of a street railway line. The first streetcar line to open in New Orleans was actually the second in the entire world, behind only a route between New York City and Harlem. The inaugural NOLA line opened in January 1835 and was called the Poydras-Magazine route, zig-zagging from Poydras Street, up Magazine Street, and finally toward the river to today’s Irish Channel.

The line was created by the New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad Company, which received a charter to build a series of rail lines that would connect New Orleans to the then-independent suburb of Carrollton. The Jackson line was the second of the series, connecting Canal and Baronne streets with the Gretna Ferry terminal where the river meets Jackson Avenue.

But it was the third line that allowed the New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad Company to fulfill its charter. The Carrollton Avenue street line began its inaugural trip up Nayades Street on September 26, 1835. Today, Nayades is known as St. Charles Avenue and the route is called the St. Charles Avenue line — the longest continuously operating street railway in the world!

Fun St. Charles Streetcar Facts

- Flagging down a streetcar is much easier now than it used to be! Here’s a message from Chief Engineer of the New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad posted in the Daily Picayune on October 18, 1838:

“Those persons who wish to take passage in the cars at any intermediate stopping points between New Orleans and Carrollton, are particularly requested to make some motion or signal to the engineer of the locomotive previous to his arriving at that point in day-light; — after dark, it is necessary, in order that the engineer may stop, that a lamp should be held out.”

- Streetcar fare also wasn’t as cheap as it sounds. The cost, in 1835, for a ride from Canal Street to Carrollton was $0.25. That’s $8.50 in today’s dollars, compared to the $1.25 it costs to purchase a ride on the streetcar currently.

- In 1835, the Poydras-Magazine and Jackson lines were pulled by horse or mule, but the main St. Charles line between New Orleans and Carrollton utilized two British built steam engines creatively called “Orleans” and “Carrollton.” There were eight daily round-trips. The first, beginning at Carrollton at 4 a.m., was horse-drawn — presumably to cut down on noise. The rest were steam-powered with the final train leaving Canal Street for Carrollton at 9 p.m.

Streetcars Everywhere

By the 1840s, the city’s population was expanding rapidly uptown of the CBD. As more houses were built along avenues like Napoleon and Louisiana, additional spurs were built along the Carrollton streetcar line to accommodate them. Increased density also increased complaints over steam-powered nuisances like soot and noise, resulting in a decades-long return to horse and mule-operated streetcars.

It wasn’t until 1961, however, that the streetcar system began to expand in other directions, as well.

One reason for this was that builders began to see streetcars as a way to generate development rather than just to service already-established neighborhoods; another was that new railroad companies were formed to compete with the New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad Company to create new lines.

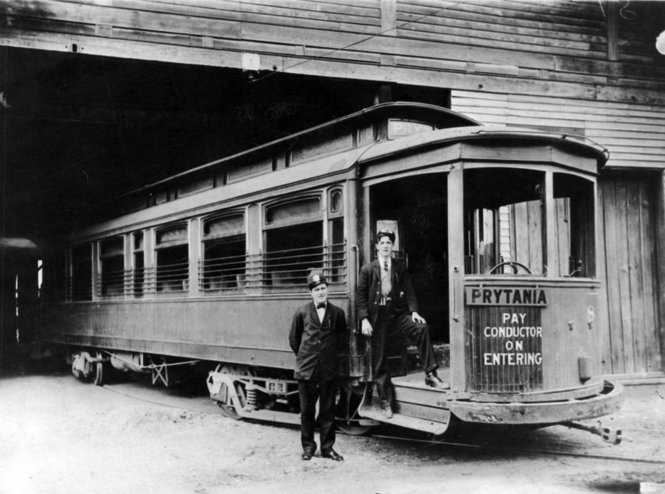

In June and July of 1861, alone, new streetcar lines began operating on Rampart and Esplanade streets, Magazine Street, Camp and Prytania streets, Canal Street, Rampart and Dauphine streets, as well as over Bayou St. John’s Bayou Bridge to City Park!

By the latter years of the 19th Century, there were six streetcar companies competing with one another for railway dominance. Each had their own iconic look. There were the white-painted cars of the St. Charles Railroad Company, the red of the Orleans Railroad Company, and the orange and yellow of the New Orleans City Railroad Company’s stock. The elder statesmen New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad Company adopted its current olive green and cream in the late-1890s. It must have been an incredible sight to see so much variety!

Of course, the city needed streetcar barns to house and service the cars of these six different companies. By 1882, there were 15 barns, in fact. That included Arabella Station, now the location of the Magazine Street Whole Foods; as well as Canal Station, the current home of the Regional Transit Authority’s main office, plus a bus and streetcar barn.

The streetcar system spread to every corner of the city, and the invention of electricity-powered streetcars — the St. Charles Line was electrified on February 1, 1893 — added speed without the nuisances of steam engines.. This was the same year the line expanded from the corner of St. Charles and Carrollton to a new streetcar barn on Willow Street. That Willow Street barn still exists today, bound by Dublin, Willow, Dante, and Jeannette streets.

Rise and Fall

But this wasn’t the last time the St. Charles line — or the city’s streetcar line as a whole — expanded. At its peak, there were more than 225 miles of street railway serving more than 148 Million people per year! Unfortunately inefficiencies that resulted from the competing companies, as well as poor relationships with employees and the advancement of buses as a viable form of public transportation led to a streetcar decline so rapid it left the city with just one functioning streetcar line by the end of 1964.

In an upcoming follow-up article, we’ll look at how the meteoric rise of the streetcar system in the 19th century soon gave way to its equally swift collapse and a controversial rebound.