We’re talking about the history of streetcars and public transportation in New Orleans! In Part 1, we charted its course from the first days of the local rail era, through the founding of the oldest continuously active streetcar line IN THE WORLD, and all the way to the vast network that eventually connected those early, isolated lines. Now, we pick up where we left off and take things to the present.

The Late 1800s

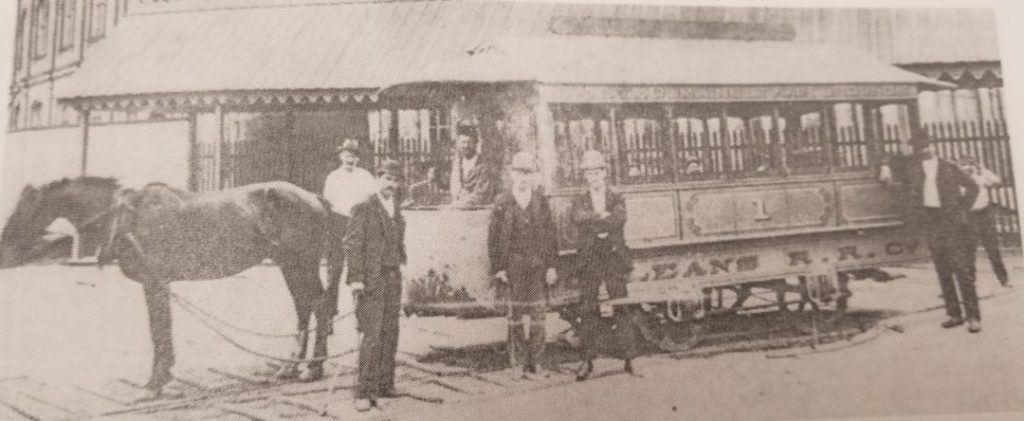

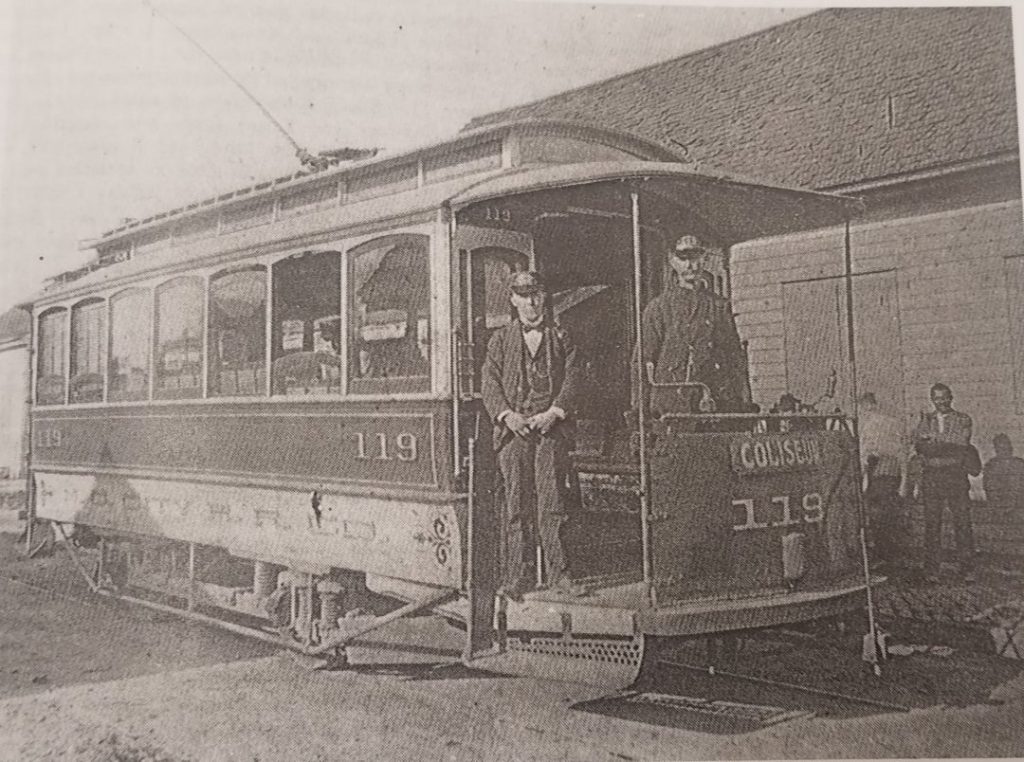

As Superintendent of the New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad Company (NO&CRR), C.V. Haile oversaw what is now the St. Charles streetcar line — then already one of the oldest street railway lines in the country.

In 1888, Superintendent Haile made a business trip to Richmond, Virginia, where he discovered how far New Orleans’ streetcar lines had fallen behind the rest of the nation. New Orleans transportation leaders saw the need for propulsion faster than horse-drawn, but bristled at the nuisance of steam power’s soot and noise.

Richmond could serve as an example. Like a growing number of light rail systems in America, the Virginia city’s utilized overhead electrical wires for power. Haile reported this to the New Orleans City Council who finally made the move and gave the NO&CRR permission to convert to electrical power in 1891.

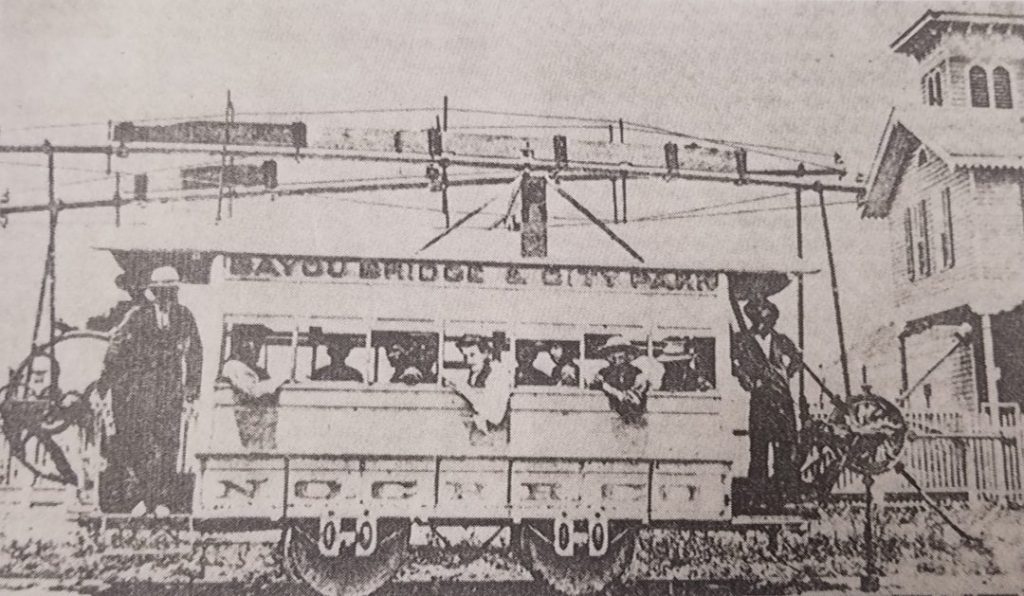

But, as we learned in Part 1, the NO&CRR was just one of many streetcar operators in the city. In the final years of the 19th century, the other companies electrified, as well, allowing New Orleanians quicker access to their jobs downtown, the suburbs upriver, the resort towns along the lake, and much more.

Decentralized System

At the end of the century, New Orleans had as many as six streetcar companies, each owning tracks around the city. In fact, sometimes competing companies owned tracks in the same neighborhood — sometimes on the same street! For example, the NO&CRR and the Canal & Claiborne Railroad Company both operated tracks along the same stretch of Canal Street.

But, besides occasionally sharing a road, these competing companies had little in common. Their cars, routes, prices, employee contracts and track sizes were all different.

Such variety among the companies created inefficiencies for ownership, as well as for their customers. For example, rather than having one route running up Magazine Street, another up St. Charles Avenue, and a few connecting those on key thoroughfares like Napoleon and Louisiana, New Orleans’ decentralized system featured competing routes zig-zagging all over Uptown, attempting to hit the key stops that would let them vie for ridership.

Coming Together

A move toward centralization finally came at the turn of the century.

In 1892, the New Orleans Traction Company formed and took over operation of the New Orleans City and Lake Railroad, as well as the Crescent City Railroad. Similarly, the NO&CRR absorbed the Canal & Claiborne in 1899, also absorbing their color scheme. The St. Charles line has been olive green ever since.

By 1900, there were only four remaining companies in the city, and — in 1902 — they were consolidated (though not merged) into the New Orleans Railways Company. At the time, it was common for municipal transportation systems to also provide utilities like electricity. NOLA was no different, which is why the New Orleans Railways Company became the New Orleans Railway and Light Company in 1905, even providing mail service.

It was a golden era for our streetcar system, but not everyone reaped the benefits. When the companies consolidated, they were permitted to keep their individual contracts with employees. This gave ownership power to operate one monopoly of a company, while keeping employees in four separate groups.

Workers struck in September of 1902 and — within weeks — won the concessions they wanted. But this, as we’re about to see, was just one of several battles fought between employees and owners.

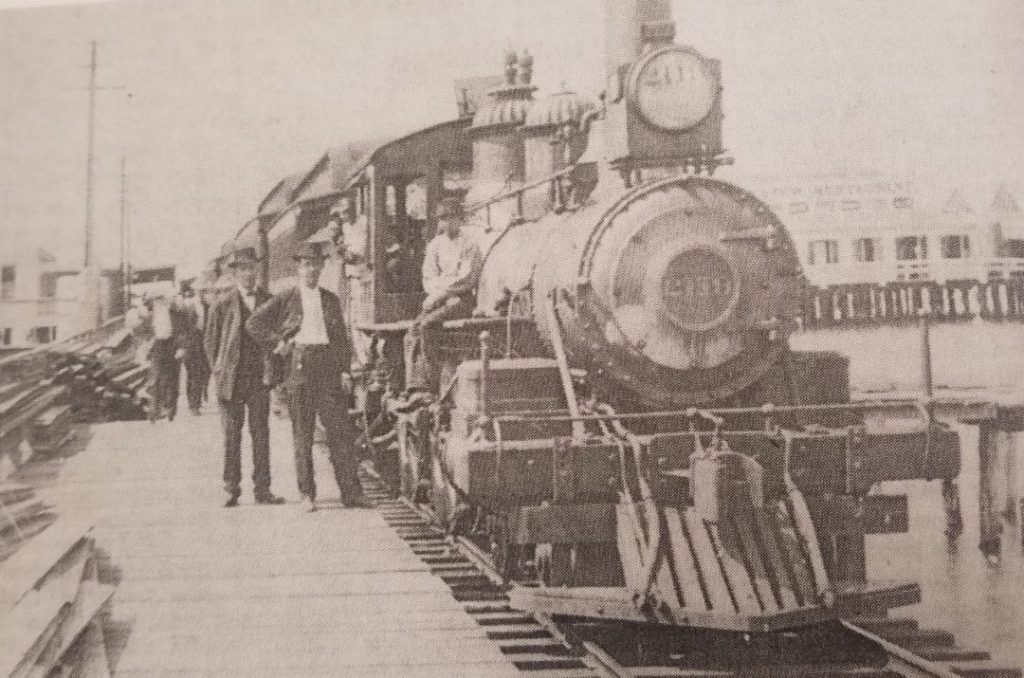

During the next two decades, the system continued to grow, expanding to neighborhoods previously untouched — including those near the 9th Ward’s newly constructed Industrial Canal. The 1920s brought the famous Desire line, as well as the Freret, Gentilly and St. Claude lines; and the creation of New Orleans Public Service Incorporated (NOPSI), which purchased all the city’s street railway, electric and gas lines.

The Roaring Twenties was the peak of New Orleans’ rail network. In 1922, NOPSI oversaw more than 225 miles of railway, and the transit system saw a ridership of a whopping 148 million people per year.

Enter the Autobus

In 1929, another strike stopped the streetcar in its tracks. This one was massive and violent, with employees wanting to curb owners’ ability to fire them, as well as a guarantee only unionized workers would be hired.

NOPSI attempted to force the streetcars back into service on July 5, but the federal marshals and police they deployed were met by mobs of strikers and sympathizers. Streetcars were flipped and men were killed.

It was one of the lengthiest streetcar strikes in American history (which also unexpectedly led to the creation of the po’boy), and — when it finally lifted — NOPSI was down $2 Million and 40 million riders. To cut costs, the Coliseum, Dryades and Tchoupitoulas lines were dropped. The Oak Street shuttle was replaced with a trackless trolley, and the St. Bernard line was swapped out with a bus.

This was the beginning of the streetcar system’s long decline. The Pontchartrain Railroad was discontinued in 1932 — 101 years after Smoky Mary made the first-ever rail trip west of the Alleghenies. It, too, was replaced by a bus, as were so many of the city’s streetcar lines. A bus, after all, only required one employee (the driver), whereas old streetcars required a motorman and a conductor. Buses cut labor costs in half!

By 1940, just 58.3% of NOPSI’s vehicle miles were on streetcars. And, at 5 a.m. on May 31, 1964, the streetcar rumbled down Canal Street for what seemed like the last time, carrying a sign that read, “See Me on St. Charles.”

The St. Charles was now the final piece of a once-massive street railway system.

National Trends

Following the emergence of buses, transit ridership actually increased. This was due to a rise in New Orleans’ population, as well as an increase in the radius a bus — which didn’t require trackage — could travel.

The system peaked at 246 million riders in 1945, but as World War II ended, there was a huge shift to the automobile. It was a trend felt across America.

Another trend was the move away from a single company that operated, both, a city’s public transit system and its utilities. Late-20th century public transit was often run by a public body that could receive tax money and qualify for federal funding. Locally, that body was the Regional Transit Authority (RTA) — created in 1979 and given control in 1983. Relieved of its transportation-related responsibilities, NOPSI became Entergy and continues to focus on utilities to this day.

A Battle Between Nostalgia and Pragmatism

“Both the historic and contemporary streetcar systems were designed to link neighborhoods to the CBD,” explains James R. Amdal, Senior Research Associate at the University of New Orleans Transportation Institute. “Back in the 1980s, when we launched the Riverfront Streetcar, it was the first project in the return of streetcars as a viable form of local public transit.”

Since then, the city has seen a measured streetcar reemergence. On April 18, 2004, the historic Canal Street line was reintroduced after a 40-year absence. And, though Hurricane Katrina flooded the barn housing all the line’s red cars, the line was back in service by December 2005.

In 2013, the eventual Rampart-St. Claude line was opened along Loyola Avenue (just days before the Superdome lost electricity hosting Super Bowl XLVII) and in 2016, the line was extended to Elysian Fields Avenue.

Even today, there are discussions and plans for new lines and extensions. But not everyone believes the streetcar — as it is utilized today — is a solution to our network’s challenges.

“Our streetcar system was designed in the 19th century to move people from Point A to Point B, but today it feels like lines are being built for nostalgia rather than utility,” explains Alex Posorske, executive director of Ride New Orleans. “They are too slow and inefficient, the routes aren’t designed to help the maximum number of people, and we seem to care more about preservation than being ADA-compliant. If this is how we’re going to design streetcars, then we’re putting gold railings on a sinking ship.”

Posorske believes the focus should be on improving our bus system, which sees high ridership compared to many other cities.

France Street is Cracking

Still, the streetcar is an important part of New Orleans history. In almost every corner of the city, one can still find remnants of that past.

On the corner of France and Royal streets in the Bywater, for example, parallel cracks can be seen turning the corner — almost definitely evidence of tracks from the famous 20th century Desire Line hidden under asphalt.

“Yeah, those cracks look like they have street rail origins,” says Edward Branley, author of several books on the city’s transit system, including New Orleans: The Canal Streetcar Line. “When they were discontinued, the city often just paved over the tracks. With our heat and humidity, the rails expand and contract, and cracks surface in the pavement.”

In fact, earlier this decade, when the road was torn up during a Bourbon Street renovation, what was found underneath it? You guessed it — streetcar tracks!

“You’ll find remnants of the streetcar network in almost every neighborhood in the city,” explains Branley.

So keep your eyes peeled next time you go for a walk and maybe you, too, will find clues to one of the earliest and most historic streetcar systems in the world.