If you’ve seen the Rex parade on Fat Tuesday it’s likely you’ve noticed the enormous white bull sitting atop one of the iconic parade’s signature floats. And you’re not alone. Decades of New Orleanians have seen the same bewildering sight. Welcome to Boeuf Gras.

The massive creature is known as Boeuf Gras and is one of the most recognizable moments of Carnival season. But what does it mean?

Like many things during Carnival, Boeuf Gras is full of symbolism that stretches back millenia. In this article we’ll explore that symbolism so that next time you see that giant cow roll by, you’ll know exactly what you’re looking at!

The most decadent time of the year

It’s not a coincidence that Mardi Gras translates to “Fat Tuesday” instead of “Slim Tuesday.” In New Orleans, we celebrate the day–and the season that leads up to it–with no shortage of alcohol, food, song, dance, and general merriment.

But Carnival season as a time of excess stretches back long (loooonnnng) before New Orleans was even a city.

Carnival, for example, comes from the Latin expression carne vale, which translates to “farewell to meat” or “farewell to flesh.” Those farewells are because Mardi Gras–Carnival’s final day–is on the evening of Lent. The Lenten season commemorates Jesus’ forty-day fast as many Christians make sacrifices of their own, abstaining from meat, dairy, fat, and sugar. It’s billed as a time of voluntary deprivation.

However, what if the origins of Lent aren’t voluntary, but necessary? In early agrarian societies, late-February and early-March were historically difficult. The year’s first crops were only starting to sprout while the meat, potatoes, and apples stored for winter flirted with spoilage. Rationing would be required, and when entering a period of want, it’s a good rule to get your fill beforehand.

That’s one of Carnival’s original purposes: an opportunity to pack on a few pounds before a period of scarcity.

Today, Catholic-dominated cultures around the world use Mardi Gras as an opportunity to rid their pantries of the fatty foods they’d typically avoid during Lent. While New Orleanians typically watch our parades with king cake, the Polish eat paczki. The British and Irish eat pancakes while the Russians have a festival dedicated to butter and cheese! And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

It’s an effort that stretches across the northern hemisphere in an effort to say goodbye to those decadent foods we enjoy so much. The Boeuf Gras is part of that tradition.

Farewell to meat

Historically, meat was one of the foods forbidden–either fully or partially–during Lent.

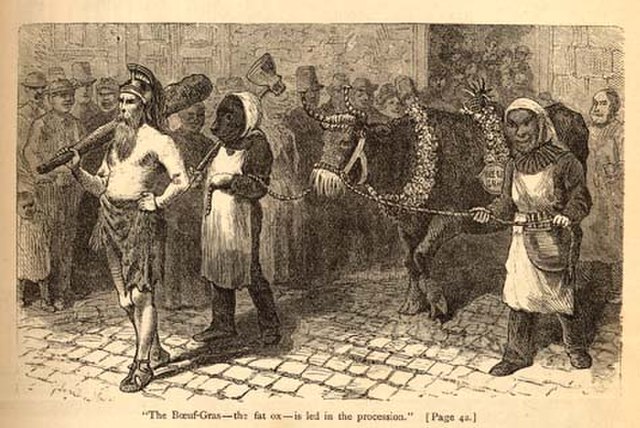

Boeuf Gras means “fatted cow” or “fatted ox” and it represented the final meat a Christian would eat before Lent. The Druids of pre-Christian times sacrificed an ox for one of their annual celebrations, but by the 1500s, Catholics in France had established a custom of parading an ox through the streets on Mardi Gras before butchering it to feed to the peasants.

The French brought this tradition to the New World and residents of Mobile, Alabama are said to have founded a Societé de Boeuf Gras in 1711, needing 16 paraders to wheel around a giant, papier-mâché boeuf gras head. (It’s important to note that some are skeptical that Societé ever existed.)

More than a century and a half later, the Boeuf Gras tradition arrived in New Orleans. During the 1867 Comus parade titled, “Triumphs of Epicure,” the parade featured krewe members in a variety of costumes representing food and drinks alongside a live bull.

Beginning with the first Rex parade in 1874, and lasting through the remainder of the 19th century, the krewe featured a live bull draped in white. Sometimes the animal was paraded in the streets, and sometimes he was secured to the top of a float. Then, in 1901, Rex himself mercifully proclaimed that his krewe would no longer use the animal in this way, stating the practice “was not in harmony with the beautiful displays which are produced in this era and (it) must be relegated to the past.”

The tradition disappeared from New Orleans for the next 50 years until 1959, when Rex announced the return of the beloved Boeuf Gras, this time in papier-mâché form.

Local artists have created several versions in the decades since, but this Fat Tuesday–like all Fat Tuesdays in recent memory–you’ll be sure to see the massive, white Boeuf Gras rolling down St. Charles Avenue and flanked by krewe members dressed as butchers and bakers. Like the massive cow, they are there as a symbol, to remind us to enjoy the decadence of the season because, in just a few short hours, Lent will be here and our time of scarcity should begin.