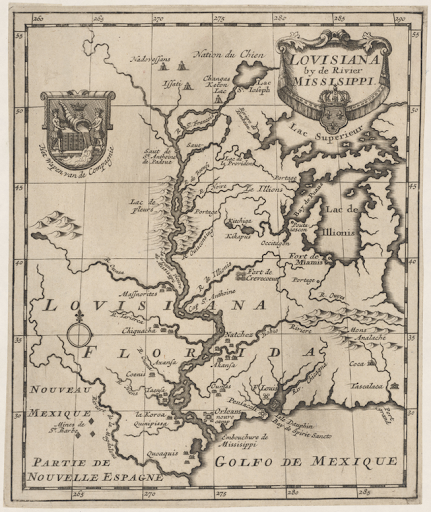

New Orleans. Lawrence N. Powell calls it “The Accidental City” in his book of the same name. Peirce Lewis memorably named it “an impossible but inevitable city” in his book, New Orleans: The Making of an Urban Landscape. Both men have a point. New Orleans was and is a very unlikely place.

We sit in swamp land, mostly below sea level, constantly threatened with flooding and other natural disasters. We’ve endured countless plagues like Yellow Fever and had to carve out our own unique identity in the early years when the city changed hands between France and Spain every few decades. Through it all we’ve maintained a sense of pride in our home based on the gutsy cleverness of those who came before us.

A Bluff for the Ages

If you’ve spent much time in the city, the name Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville will be familiar. Called the Founder of New Orleans, his is a prescient presence throughout the city. His portrait can be seen in numerous shops, bars, and a fine oil painting of him is housed in the Historic New Orleans Collection on Royal Street.

From that famous portrait it’s easy to forget that Bienville was ever a young man. But, in fact, he was only 12 when he signed up for the French Navy and 17 when he joined his brother Iberville’s expedition to explore the land around the Mississippi River in 1697. The group established a colony close to what is now Biloxi, Mississippi and Bienville was made second-in-command when Iberville returned to France in early 1699.

Later that summer, while exploring further up the river, Bienville encountered the Carolina Galley, a British corvette with 10 cannons and commanded by a familiar face, Captain Louis Banks (or Bond depending on the source). Banks had been taken captive by Iberville only two years before during King Phillip’s War and recognized Bienville as well.

Although Bienville had only five men and two bark canoes, he nevertheless paddled out to the British ship and informed Captain Banks to leave the area immediately as just upriver French fortifications would destroy his ship if he did not. No such fortifications existed. Also, the sly 19-year-old told the older Brit, the captain wasn’t even on the fabled Mississippi River. Like La Salle some years before, the captain had overshot the river’s entrance and was firmly in French claimed territory.

Banks, no doubt remembering his treatment as a prisoner of war, decided to take no chances and turned the ship around, sailing out into the Gulf, and away from the Mississippi. The area became known as English Turn and, although no forts existed there in 1699, a few short years later two were built across the river from each other there. Without Bienville’s quick thinking, the area now known as New Orleans would have been British territory and Bienville wouldn’t have founded our port city in 1717.

12 Miles Downriver

Nearly 100 years after the founding of New Orleans, the city once again found itself facing down the British, this time during the War of 1812. Sometimes called the Second War for Independence, the British were determined to capture the ports of the Mississippi and cut off supplies traveling the river. General Andrew Jackson arrived to defend New Orleans from the 15,000 British troops with only a few hundred soldiers.

Jackson recruited Creole and Spanish Louisiana militiamen, 1300 sharpshooters from Tennesse, Jean Lafitte and his band of privateers known as Baratarians, and over 500 free People of Color to fight along the banks of the Mississippi some 12 miles downriver of New Orleans in Chalmette. This particular location was ideal for Jackson’s purposes as the river on one side and a large swamp on the other offered only a very narrow plot of land for the battle, essentially creating a bottleneck to trap the British in.

On January 8, 1815, the British arrived to find Jackson’s army behind ramparts and ready for battle. Although the British were exhausted after marching for days in mud up to their knees and hauling cannons through swamps, they remained certain their better trained soldiers (and superior numbers) would clear out Jackson’s army without any trouble.

The British commander, Sir Edward Pakenham, made the mistake of sending his men straight at the entrenched Americans without ladders to climb the ramparts. The British soldiers were caught in what some termed a “turkey shoot” and suffered over 2000 casualties and a terrible defeat. Jackson’s army, on the other hand, only lost 20 men making the Battle of New Orleans one of the most lopsided military wins in history, and securing the safety of New Orleans and the newly formed United States of America.