No one does Mardi Gras like New Orleans. We’re known worldwide for our lavish displays of excess in the parades, costumes, and parties that abound during Carnival season. King Cake parties and days of eating gumbo with family give way to the final spectacle of Fat Tuesday when Zulu and Rex rule the day and masked revelers overwhelm the streets. Mardi Gras has been celebrated for centuries in New Orleans but many don’t realize just how close the tradition came to being outlawed in the 1800s.

Chaos Reigns

The first Mardi Gras in Louisiana took place in 1699 when the Le Moyne brothers, Iberville and Bienville, observed Fat Tuesday as part of their Catholic practices. Mardi Gras had been made an official holiday by the church in the 1500s as a way for people to celebrate and indulge themselves before the 40 days of fasting and praying for Lent which precedes Easter.

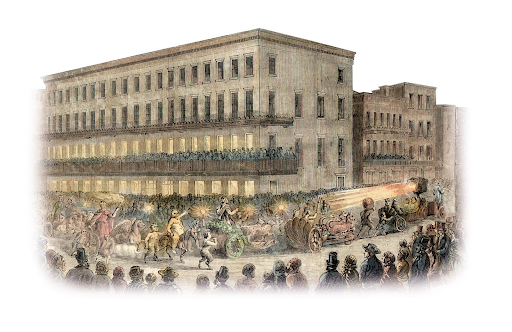

The exact date of the first Mardi Gras in New Orleans is unknown. But the practice was well established by the 1730s. People dressed in costumes and masks to hide their identities as they celebrated the day. Processions of people made their way through the streets to parties and balls and ladies threw bonbons and other sweets to the revelers from carriages. Young people threw flour at each other and over the processing people until the streets looked as if they were covered in a fine layer of snow.

All of this was commonplace for the French residents of New Orleans. It was with the arrival of the Spanish, and later the Americans, that the rowdiness of Mardi Gras day began to be met with displeasure from the civic government. By the 1850s, Mardi Gras was in danger of being outlawed as the usual throwing of flour had been replaced by the hurling of bricks at people and property. Brawls between the French Catholics and the Protestant Americans were breaking out with more frequency and the more genteel parts of society began to fear Mardi Gras day. Clergy and politicians began to call for an end to the ancient tradition from the pulpits and the press.

Secret Societies and Planned Revelry

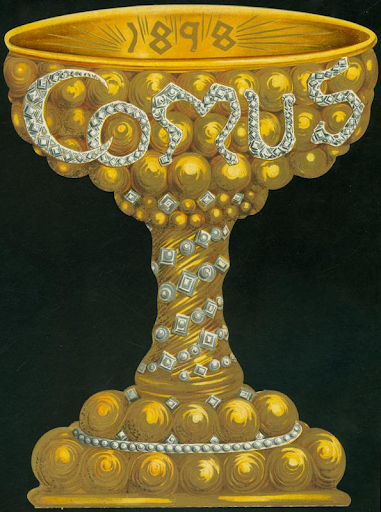

Just as it seemed the fate of Mardi Gras was sealed, a group of six businessmen from Mobile, Alabama gathered together with their friends to create a secret society in an effort to bring some order to the chaos of Fat Tuesday. In 1857, these Anglo-Americans formed the Mistick Krewe of Comus, named after the famous “Lord of Misrule” from a play by John Milton. These men planned a grand ball and a parade for Mardi Gras night.

The first Comus procession featured two elaborately decorated floats with the theme The Demon Actors from Milton’s Paradise Lost. The krewe paraded down Canal Street with torches to show off their costumes and marching bands to enchant the crowd. The themed floats and costumes were such a hit with the revelers that the story of the Comus procession spread beyond the city and the next year thousands of visitors came to New Orleans just to see this Mistick Krewe in their second foray down Canal Street.

Largest Free Party in the World

Seeing the success of Comus, other organizations soon followed. Rex, Momus and Proteus began to parade just a few years later and while Comus no longer parades, Rex and Proteus do. Rex even meets with the Royal Court of Comus each year as a show of respect to the original krewe and as a symbolic end to the Carnival season.

By organizing the first Krewe in New Orleans, Comus created the template Mardi Gras celebrations follow to this day. The Mistick Krewe of Comus not only helped to save Mardi Gras from being banned, it has helped the City of New Orleans become host to the “largest free party in the world” for more than 160 years.