Surely there are loads of New Orleanians counted among New York City’s 8.5 million residents. But I’d bet few, if any, are so scandalous as Madame X.

To be fair, she doesn’t live in New York. She doesn’t live anywhere, actually. She passed away on July 25 of 1915. But a painting of the controversial woman, Portrait of Madame X, resides in the Big Apple’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it arrived the year after its subject’s death.

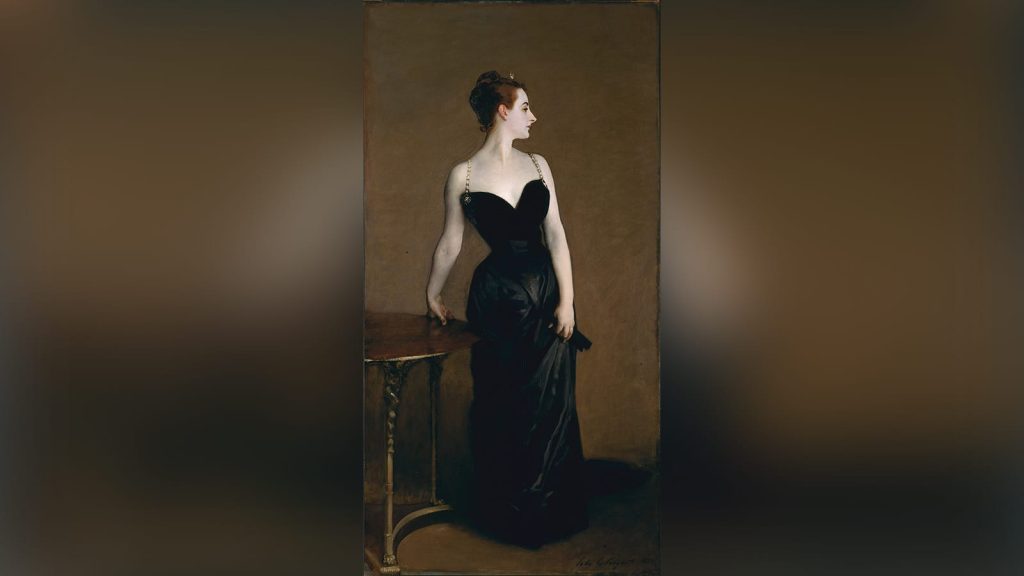

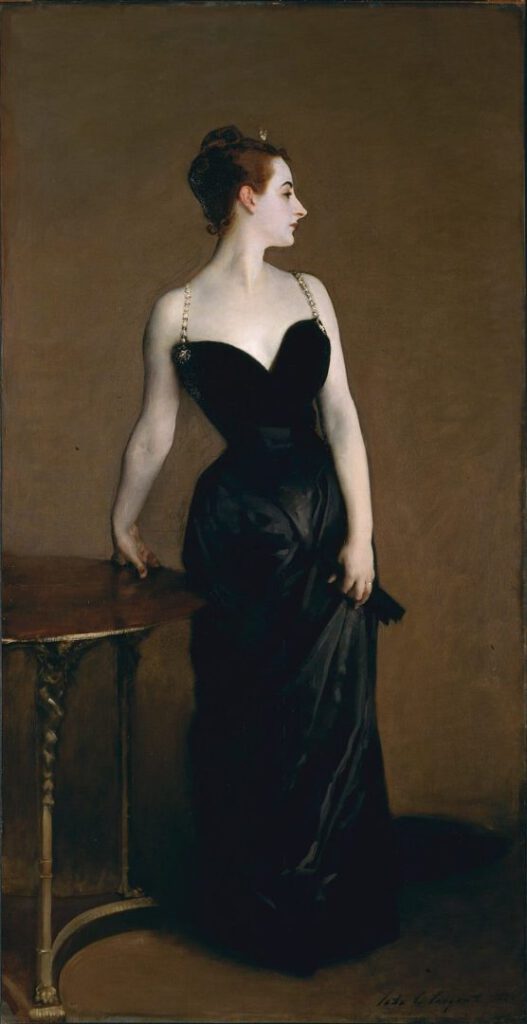

You might not guess by looking at it, but this painting created an uproar that shot through the highest levels of Parisian society. Its unveiling in 1884 was met with such disdain that the painter fled in shame to London and the subject’s mother begged for the portrait to be removed from the highest-profile art exhibition at which it was displayed.

But what is it about Madame X that elicited such a strong reaction? Sure, there are what feels like miles of bare skin between her hair — pulled up high off her shoulders — and the sensual black dress low enough to reveal her decolletage. That by itself, however, wouldn’t have been enough to make the women and men of Paris blush.

Nude female portraits had been gaining popularity in France for much of the 19th century. A full two decades earlier, paintings like Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia helped to normalize nudity in art.

And Madame X, of course, was quite far from nude.

So why were French eyes so horrified by the sight of this mysterious New Orleans woman in a sexy — but relatively modest — black dress?

That is part of her mystery.

Who Was Madame X?

Virginie Amélie Avegno was born in New Orleans on Jan. 29, 1859, and went by Amélie. It is rumored that she lived her early years in the mansion at 927 Toulouse St. in the French Quarter (a few doors down from where Fahy’s Irish Pub now stands).

The young Creole girl was the daughter of Marie Virginie de Ternant — a descendent of French nobility who grew up at the historic Parlange Plantation House — and Anatole Placide Avegno of Italian ancestry.

Mr. Avegno served as a major in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War, commanding a battalion with soldiers from a famously wide variety of ethnic backgrounds that included French, Spanish, Mexican, Irish, Italian, Chinese, German, Dutch and Filipino.

Amélie was just 3 years old when her father died at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee. This was devastating to the family, and four years later, in 1866, tragedy struck again when her sister died of yellow fever.

Fortunately, they still had plenty of money, unlike many Southern families immediately after the Civil War, so looking to move on from grief, Amélie’s mother moved herself and 8-year-old Amélie to Paris, where the family kept an apartment.

As she grew into a young woman, Amélie, along with her mother, had ambitions to reach the highest levels of French society. She was educated in Paris, and was introduced into the company of those with a more lofty social status — but always with her vigilant mother nearby. That changed when she was married at 19 years old to Pierre Gautreau, a French banker and shipping magnate.

Now, out from under her mother’s watchful eye, Amélie became one of Paris’ stand-out beauties. She wasn’t conventionally ravishing by French standards, but her uniqueness is likely what caught men’s attention. Her very pale skin was her defining feature, and she used lavender face and body powder to enhance her complexion. She even consumed arsenic to further sap her skin of color, and dyed her hair with henna as contrast. She wore clothes that accentuated her curvaceous figure and exposed her long, slender neck.

Amélie attracted a lot of attention, and she didn’t exactly push that attention away. Her extramarital affairs were the frequent subject of tabloid scandals and gossip, and she became the obsession of many-a-man.

One American expatriate, artist Edward Simmons wrote, “I remember seeing Madame de Gautrot [sic], the noted beauty of the day, and could not help stalking her as one does a deer. Her head and neck undulated like that of a young doe…Every artist wanted to make her in marble or paint.”

One admiring artist was about to get his chance.

A Portrait

Despite having admirers, and even a New York Herald article about her titled, “La Belle Americaine: A New Star of Occidental Loveliness Swims into the Sea of Parisian Society, ” Amélie struggled to break into the upper echelons of her adopted home city. This was in large part because she was a Creole American.

Eager to raise her standing, she thought it would help to have her portrait painted. But she needed to find the right artist.

Young painter John Singer Sargent was another American living in Paris. He had painted portraits for several other expats, but he, like Amélie, yearned for French acceptance. In 1877, his large portrait of a young woman named Fanny Watts was hung in a featured position in Salon, Paris’ most important art exhibition. Sargent’s reputation grew, but he needed to paint a subject who could elevate him to the next level.

Amélie was Sargent’s desired muse, and he reached out to one of their mutual friends — likely one of Amélie’s extramarital interests — to put in a good word. Sargent offered to paint her portrait for free, and Amélie was happy to accept. It was a match made in heaven, two American expats in their late-20s hoping to improve their social standing.

It took 30 sessions in 1883 to complete the painting, and — just as he had insisted on for other portraits he’d created — Sargent picked the dress.

The black dress was chosen from Amélie’s wardrobe and made to fit tightly around the hips. It was eloquent and suggested wealth and high status. Amélie pulled at the dress with her left hand, on which her wedding ring was displayed.

But this is not a painting about an affluent, married woman.

Poet and art critic Eli Siegel said of Portrait of Madame X: “All beauty is a making one of opposites; and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

To Siegel and many others, unifying contradictions within is at the heart of Madame X. On one hand, we have an aristocratic, married woman. On the other hand, she is posed flirtatiously. Her high hair, low-cut dress and lack of jewelry exposed her famously pale skin, and — in the original piece — one of the dress’ straps had fallen off Amélie’s shoulder.

It wasn’t just that the woman was upper-class or married. It wasn’t just that she was posed seductively and inviting attention. It was that she was both at the same time.

The painting was accepted into the Salon’s 1884 exhibition and for better or worse, at nearly eight feet tall, it would stand out in the exhibition’s crowded walls.

The Aftermath

Amélie believed Sargent had created a masterpiece. Parisians and art critics, however, didn’t see it that way. Almost as soon as the Salon opened its nearly two-month show, critics voiced their disapproval.

They said her pale-blue skin tones resembled that of a corpse. A French newspaper, L’Événement, wrote that, “When one stands 20 metres from the painting, it looks like it might be something. But when one gets closer…one realises that it is only hideousness.”

The New York Times critic in Paris wrote, “Sargent is below his usual standard this year. His portrait of the so-called beautiful Mme Gauthraut [sic]…is a caricature. The pose of the figure is absurd, and the bluish coloring atrocious.”

Painter and subject were both mocked and satirized in fake advertisements and false letter campaigns. The painting was caricatured in Paris’ popular Le Charivari illustrated magazine. Scornful Parisian women criticized Amélie for being a “professional beauty” — meaning she worked hard at being beautiful at a time when upper class women were not supposed to work hard at anything.

Even Amélie’s own mother tried to convince Sargent to remove the painting. The painter refused, but tried to convince the Salon to allow him to repaint the strap higher on her shoulder. They, too, refused.

The criticism was sustained and intense, with a French critic writing that if one stood before the portrait, they “would hear every curse word in the French language.”

It turns out the French were tolerant of adultery among their upper class, as long as they weren’t brought face-to-face with it. Rather than lifting Gautreau and Sargent into the highest rung of society, it forced them both into hiding.

Amélie stayed out of the public eye until the scandal had blown over, but when she returned she found she was no longer desired in the same way. She was painted several more times in the 1890s, but neither work was given the attention Sargent’s garnered. As her beauty faded, she was said to become a recluse.

As for Sargent, he left France in shame, moving to London and, eventually, New York City. Slowly, his star began to rise again.

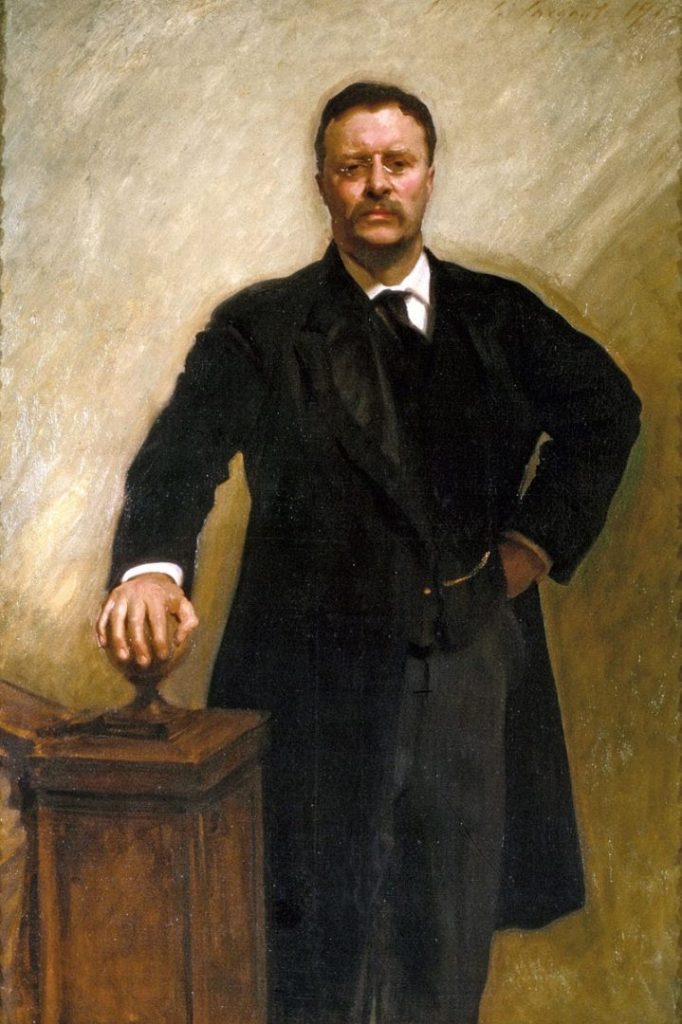

By the end of his career, Sargent was considered by many to be the leading portrait painter of his generation. He was commissioned to create portraits for Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, as well as other notable Americans such as John D. Rockefeller.

But Portrait of Madame X remains his most controversial and famous piece. In 1915, Sargent agreed, saying, “I suppose it is the best thing I have ever done.”

The following year he sold the painting to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art for $1,000 — which is where it remains today.

Portrait of Madame X remains a popular piece at the museum and continues to inspire some of the most creative minds in fashion, literature, music and art. So next time you find yourself in New York, be sure to pay a visit to this notable New Orleanian.