Include a Topper!

Happy Birthday Banner

$9.00

Add Ons

Your cart is currently empty!

Since 1949 celebrating 75 years. Order online or call us at 1 800 GAMBINO (426-2466)

Twelfth Night — or January 6 — is the undisputed kick-off to Carnival season!

But the Twelfth night of what?

In many parts of the world, Twelfth Night and the Christian holiday, Epiphany, are synonymous. One definition of epiphany is “the manifestation of a supernatural being.”

In this case, that supernatural being was the baby Jesus, who manifested himself to the Three Wise Men (a.k.a. the Three Kings). Those kings had been following the path of a mysterious star for several days. And on January 6 — on the twelfth night after the Christ Child’s birth — that manifestation finally occurred.

Ahhhhh, that makes sense! So, the 12 Days of Christmas signify the 12 days between when Jesus was born and when the Three Kings found him. December 25 (1)….December 26 (2)…. December 27 (3)… wait… that puts the twelfth day of Christmas on January 5.

It all depends on when you start counting. Half the world — in places like England — include Christmas Day. The other half of the world — including America — begins counting the day after Christmas.

Which brings us to January 6. The final day of the Christmas season.

Of course, in modern day New Orleans, that’s nothing to get too bummed about because it also marks the first day of Carnival season! Here’s a brief look at a few of the ways we celebrate this momentous day and from where those traditions come.

In 21st century New Orleans, January 6 is traditionally the first day you’re allowed to eat king cake. Because, to us, king cake is a Carnival season treat.

But for the first 200 years or so of our existence — and still in most other Catholic countries — king cake isn’t related to Carnival. It’s related to Christmas. In fact, for early Christians, king cake was only eaten on Twelfth Night.

It wasn’t that long ago that “king cake” was actually called “kings cake,” named after the Three Kings to which Jesus revealed himself.

Christianity officially began celebrating the Feast of the Nativity (which we now call Christmas) for 12 days beginning in 567 AD. Epiphany was second in importance, only to Christmas Day, itself. In England — both among royalty and commoners — Twelfth Night feasts included a large cake, called “Twelfth Cake,” that had a bean hidden in it. Family and friends were assembled, the cake was divided, and whoever picked the piece containing the bean was accepted as king for the day, called “King of the Bean.” Occasionally a pea was also hidden, and whoever found the pea would be crowned queen.

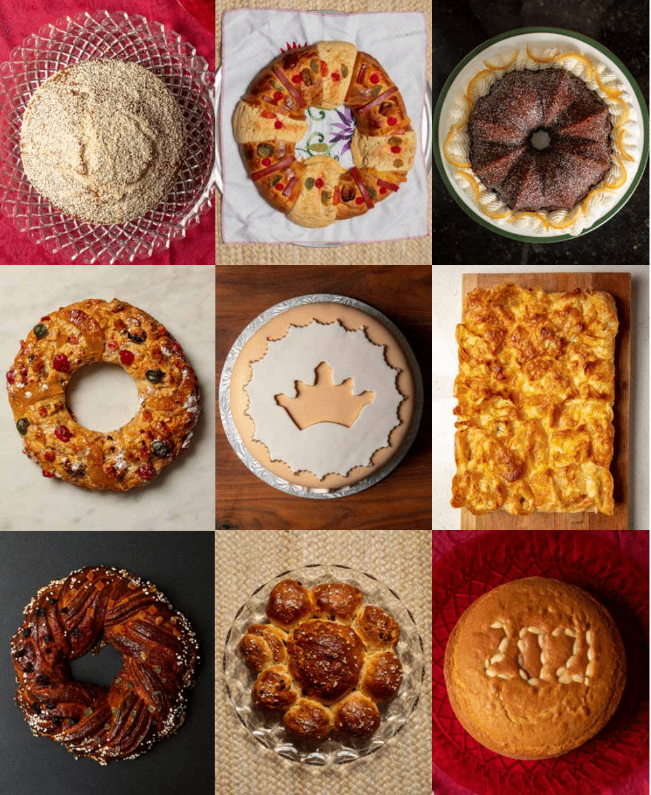

It’s not just the English who had this tradition. To this day, the Spanish eat Roscón de Reyes and the French enjoy Galette des Rois and Gâteau des Rois. Germans and Swiss eat Dreikönigskuchen, while the Portuguese celebrate with Bolo-Rei.

And each of those cakes translates to “cake of kings” or “kings cake.”

But the tradition goes back even further. Before the Christians. As far back as four thousand years ago, the ancient Romans celebrated their raucous Saturnalia festival (which commemorated the Winter Solstice and, not by coincidence, is exactly the same time of year as Christmas) by hiding a bean in a cake. Whoever found the bean in their cake was crowned queen or king of the Saturnalia!

In the earliest years of the tradition, that queen or king was sacrificed to the gods after their reign. So next time you find the baby in your Gambino’s king cake and have to buy the next one, don’t complain. It could be worse!

Beginning at 6:30 p.m., the Phunny Phorty Phellows will gather with costumes and instruments at the Willow Street streetcar barn near Carrollton Avenue. At 7 p.m., they board the streetcar and head down the St. Charles Avenue line to “herald the arrival of Carnival!”

But it wasn’t always this way.

The Phunny Phorty Phellows began way back in 1878, and their slogan, “A little nonsense now and then is relished by the best of men!” positioned them as something different than the more serious, traditional parades of the time. From then, on and off until 1898, the Phellows followed Rex, prompting one historian to call them, “The Dessert of Mardi Gras.”

Unfortunately, there was no dessert for the next 83 years, from 1898, all the way until 1981, when a group from Krewe of Clones (who claim credit for Krewe du Vieux), revived the Phunny Phorty Phellows tradition by ending Mardi Gras.

The following year, however, their role in Carnival changed to what it is today: rather than signaling its end, they kicked it off.

In a season known for king cake, maybe there’s nothing wrong with eating dessert first!

At the same time the Phellows begin their streetcar journey the annual Joan of Arc Parade will begin winding its way through the French Quarter.

The Joan of Arc parade has been rolling for just over 15 years, but Twelfth Night’s relationship with parading extends far beyond that.

In early Christian Rome, a hideous figure, known as Befana, paraded the streets each Epiphany. Roman children, upon going to bed, hung up a stocking. The next morning, the good children discovered Befana had filled their stocking with cakes and sweetmeats. The naughty children, on the other hand, found theirs stuffed with stones and dirt!

Sound familiar? She’s basically Italy’s Twelfth Night equivalent to St. Nicholas.

But who was Befana?

Once again, it always goes back to those Three Wise Men.

They were on their search for the baby Jesus, and, while passing through her town at night, they learned Befana was considered the town’s best innkeeper. Exhausted, they stopped in at her home, and asked if they could stay for the night.

The next morning, the three men — impressed with Befana’s work — asked the innkeeper if she wanted to join them on their quest to find the son of God. She declined, however, citing a backlog of housekeeping.

“Hi, do you want to come with us to meet the Lord and Savior?” I imagined the wisest man asking.

“No, I have to clean the baseboards,” Befana scoffed with a hand on her hip. “If I don’t do it, no one will.”

Legend has it that, that night, it occurred to her that she may have made a poor decision. Befana tried to find the three wise men again, but was unable. To this day, she is still searching for the baby Jesus, leaving treats (or dirt) on Twelfth Night for kids as she passes by.

Parades have featured Befana since the days of early Christianity and continue to do so today In Italy, and in many Italian communities around the world.

But the practice of parading on Epiphany has since spread far and wide. In 1870 that tradition extended to New Orleans with the Twelfth Night Revelers, a group that still exists today.

A writer for The Daily Picayune described the scene at the Twelfth Night Revelers’ second parade — an ode to nursery rhymes — in an article from 1871:

“How joyfully the children looked at the fairy spectacle; how merrily did they laugh, and how gleefully they shouted when before their eyes passed the real heroes of the simple stories to which they had always so attentively listened. And older folks imagined themselves, again little children with hearts undisturbed by the world’s troubles and life’s cares.”

Think of your favorite Carnival parade and you might sense a similar atmosphere.

The article goes on to explain nearly every passing character, from Humpty Dumpty and his wagon of brooms to Mother Goose and her fond children, to sweet little Bo-Peep “in the barb of a shepherdess,” and Jack and Jill “going for water as it were.”

This January 6, 152 years later, the Twelfth Night Revelers will meet downtown to continue their long standing tradition. By 1880, they were no longer parading, but they have held a ball every year since they began, and some of their traditions will feel familiar.

When you pick up your king cake in the morning, the past queens of the Twelfth Night Revelers will meet at Antoine’s for their annual luncheon. As you bring the king cake to your Twelfth Night party, the Revelers’ Lord of Misrule will ride through the French Quarter on horseback, making his way to the ball at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel.

When you watch the Phunny Phorty Phellows buzz by on their streetcar, the Revelers’ costumed junior cooks will be handing out programs to guests, and when you’re watching the end of the Joan of Arc parade, cooks at the Ritz will roll out a giant cake — one hiding a golden bean — and they will distribute slices to the young ladies at the ball, one of whom will become queen.

A lot has changed over the centuries. It’s equally amazing how much has stayed the same.