Include a Topper!

-

Happy Birthday Banner

$9.00

Add Ons

Your cart is currently empty!

Since 1949 celebrating 75 years. Order online or call us at 1 800 GAMBINO (426-2466)

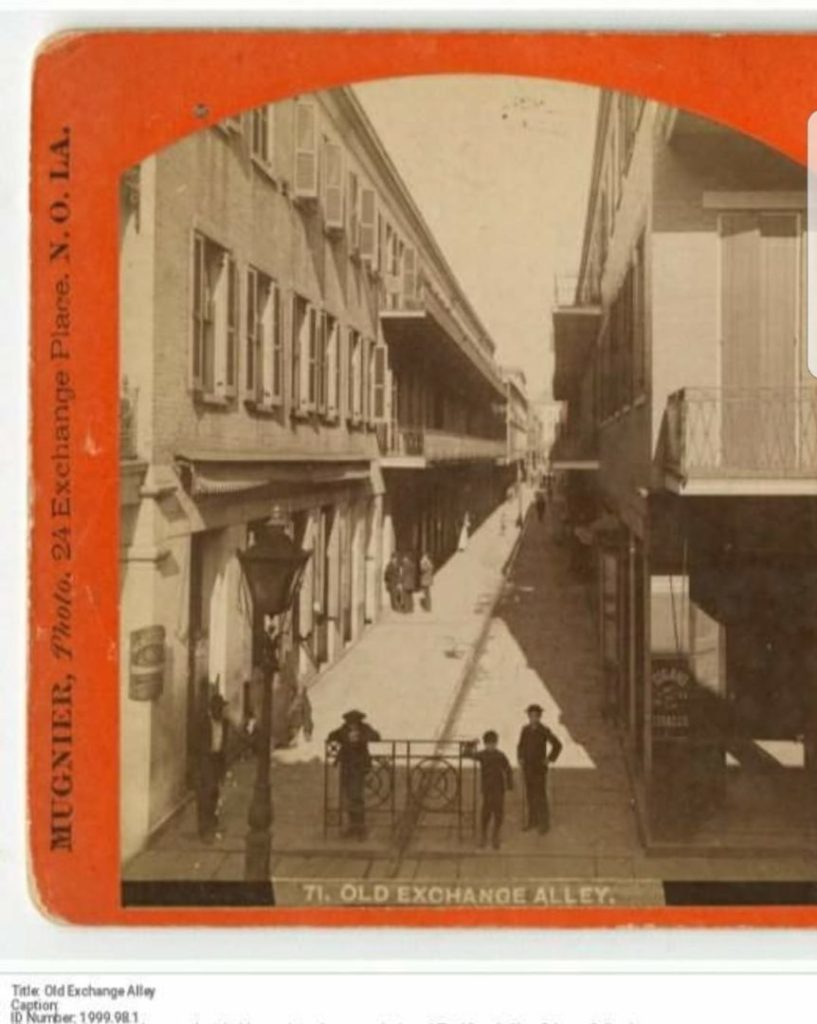

If you have taken the time to walk through the French Quarter, you might discover a very special alley, running from Canal Street down to Conti Street and sandwiched between Royal and Chartres.

This mysterious, easy-to-miss passageway has been called Exchange Place, Exchange Alley, and Exchange Passage. And it just so happens that this tiny street can tell us an enormous amount about New Orleans’ history in the 19th century.

But what is being “exchanged?” Where did the name come from?

We are glad you asked.

Before the Civil War, exchanges were some of the most important buildings in American cities—particularly in a port town like New Orleans. Here’s how local historian, Richard Campanella describes exchanges in a piece he authored for the Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans:

“They were essentially places where people met to conduct business. But because the assembled parties usually had other needs and desires—for banking and legal services, reading rooms and studies, lodging, recreation, entertainment, victuals and libations— exchanges accommodated a much wider range of programming.”

Nineteenth century entrepreneurs created ornate multi-use, multi-service spaces with a variety of amenities catering to hardworking businessmen. As a result, an exchange became a key piece in a city’s social and economic geography.

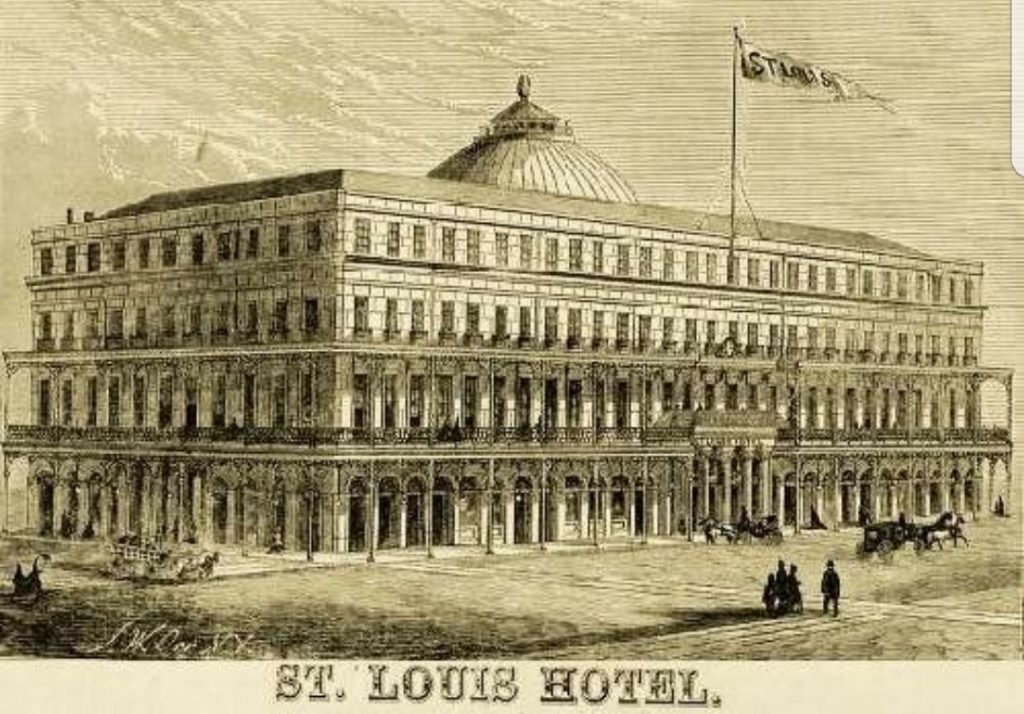

Most of the opulent hotels in antebellum New Orleans, such as the St. Charles and the St. Louis, billed themselves as exchanges. Imagine something like the equivalent of modern conference hotels, but exchanges were much fancier.

A passageway to what?

Exchange Passage—today known as Exchange Place—was created in 1831 as a small street in the French Quarter. It was not a part of Bienville and Pauger’s original plan for the city that was laid out a century earlier. Rather (and this is very important to remember) Exchange Passage was added as a discreet route between two of New Orleans’ most important 19th-century exchanges.

At the time of the passage’s founding in the early 1800s, New Orleans was said to have one of the highest occurrences of fencing duels in the world. Young, wealthy men would flock to Exchange Passage to study fencing with the masters who worked on the street.

But shouts of “En garde!” were soon replaced by murmurs of, “Can you spare a nickel?” The destitute moved in, while the swordsmen took their studies to other parts of the city.

Fortunately for the city’s beggars, the businessmen traveling between exchanges had more money to spare than your average resident. Dressed in suits, they would move back and forth from business to business, bank to bank, and barroom to barroom, a hidden economic engine powering so much of this city.

A tale of two cities

Exchange Place has always begun at Canal Street. Today, a sign for “Exchange Alley” marks the spot. It is a narrow road, used by the occasional garbage truck or frustrated motorist sandwiched, humbly, between a Popeyes Chicken and a VooDoo Mart advertising a 24-hour ATM.

But this alley wasn’t always so humble.

After the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 made New Orleans an American city, Anglo-Americans flocked here from northern cities. As more arrived, their influence grew and challenged what had previously been Creole dominance.

Banker and merchant, Samuel Jarvis Peters, thought it would be savvy to build an exchange closer to Canal Street. (Canal Street was the dividing line between the city’s Anglo population on the CBD/Uptown side and the Creole faction on the French Quarter/Marigny/Bywater side.) Peters hoped that building an exchange close to Canal would help shift economic activity in the Anglo-Americans’ favor.

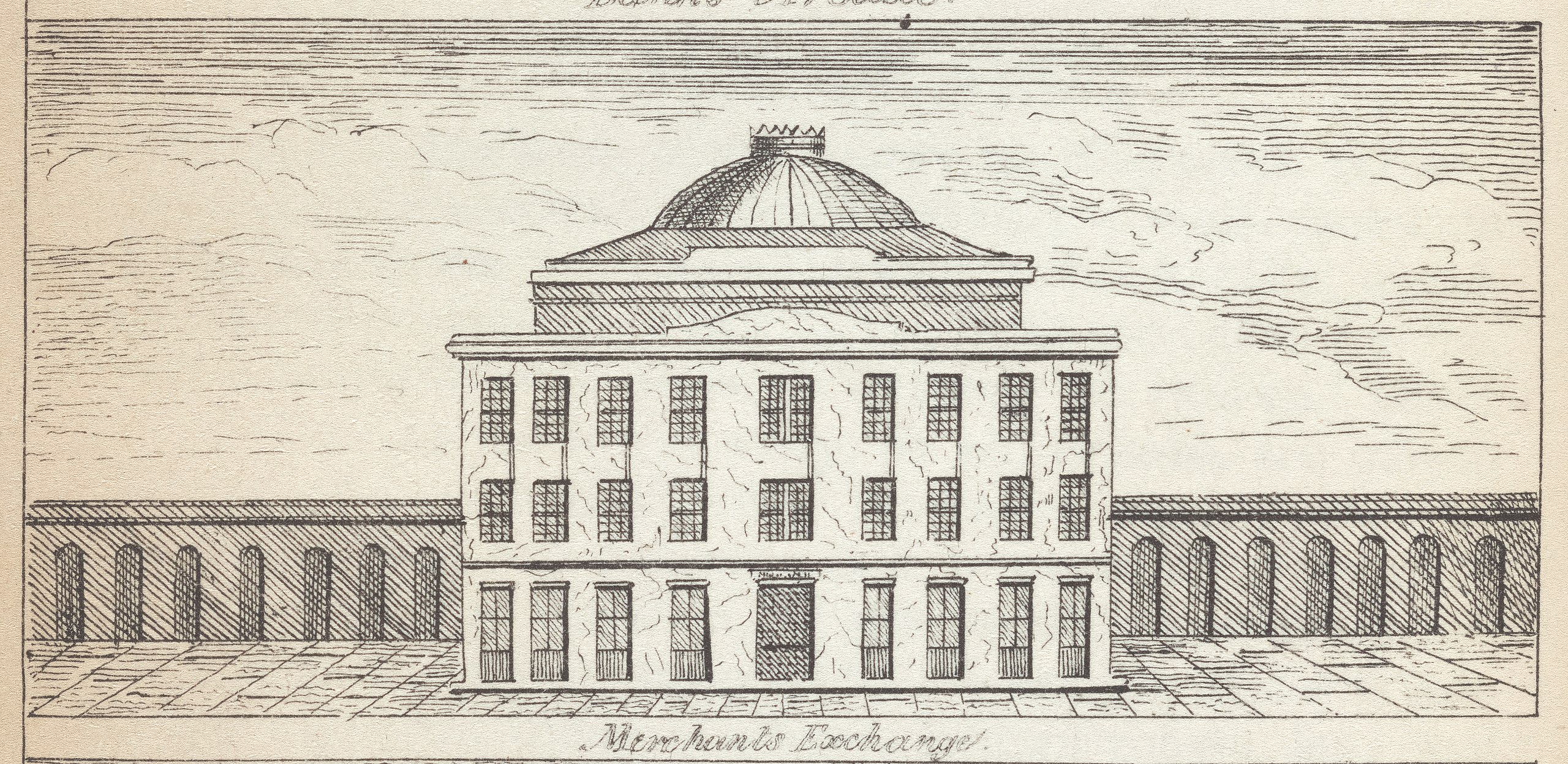

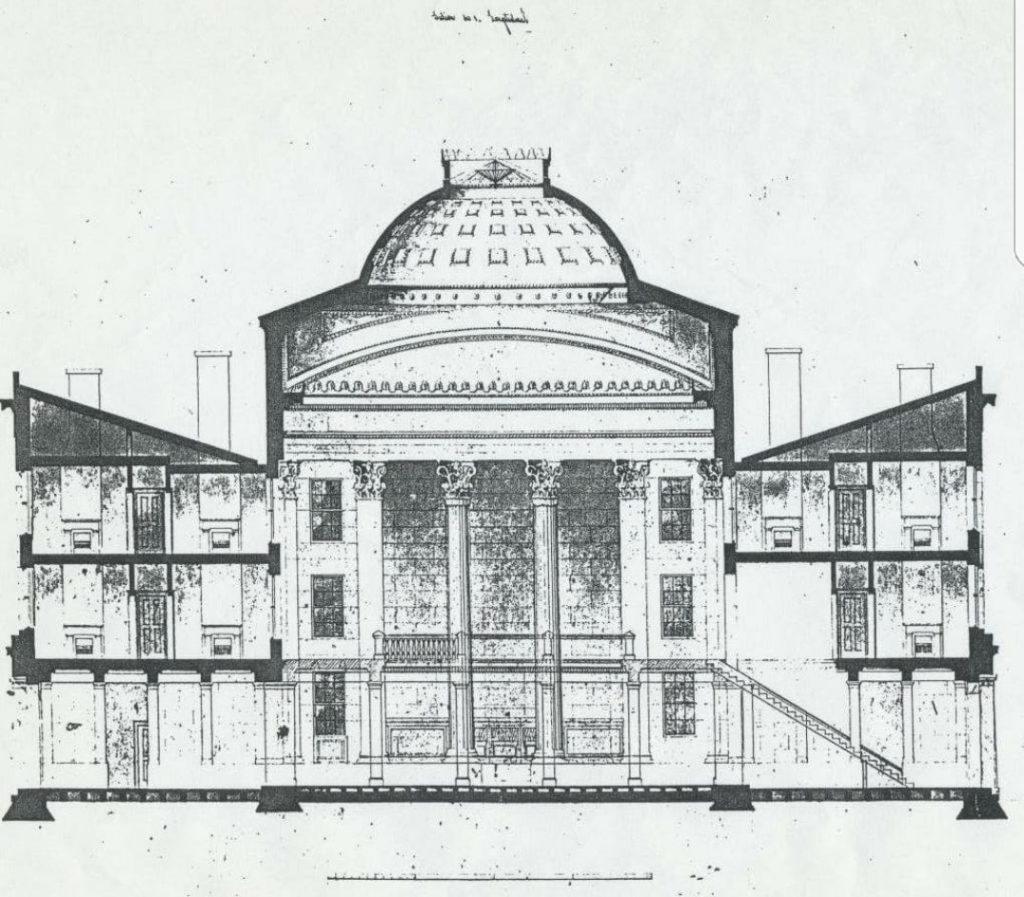

Thus, the “Merchants Exchange” was commissioned on Royal Street (at what is now 124-132 Royal) in 1835, and Exchange Passage was an often used back entrance into the building. The architect was none other than James Gallier, Sr., the Irishman also responsible for Gallier Hall, the Pontalba Buildings, St. Charles Hotel, and Government Street Presbyterian Church.

Because they were meant to show wealth, the exterior of exchanges were often ornate affairs. It is said, however, due to space limitations, the facade of the Merchants Exchange was left relatively plain, designed in a Greek Classical style. The interior, however, according to historian Campanella, was anything but plain:

“What awaited inside would astound the visitor: a spacious rotunda uniting the two wings, topped with a stunning dome and florid skylight. Architectural historian Samuel Wilson Jr. described it as ‘one of the first great monumental interior spaces ever seen in New Orleans,’ a soaring atrium bathed in natural light surrounded by walls with towering pilasters and Corinthian capitals.”

The Merchants’ Exchange would host a head-spinning array of uses, programs and occupants. In today’s parlance, Campanella called it a “shared space: flexible public space held in the private domain for multiple users day and night.”

There were auction rooms, meeting areas, trading floors, a post office, and a bar that made a killing off of the foot traffic the other activities in the building created. For $10 per year, patrons had access to the second-floor reading room “stocked with the latest tomes and newspapers,” plus two bulletin boards displaying ship information and the most important news of the day.

Unfortunately, commerce—on which exchanges depended—was slowed because of the blockades of the Civil War. The struggles continued once the war ended along with the South’s slave-based economy.

Exchanges fell out of favor, though the Merchants’ Exchange building wasn’t destroyed until a fire ravaged it in 1960, resulting in its demolition shortly after. Today, the historic space houses a Wyndham Hotel—bustling, but barely a shadow of its former glory.

A vibrant thoroughfare

From Canal Street, Exchange Place crosses Iberville Street. There, our alley takes a slight jog to the right.

After crossing Iberville, the road is more narrow than it was a block earlier. Still, it is mostly used as a place for Royal Street establishments (we’re now behind the Hotel Monteleone) to store their trash.

So far, Exchange Place has seemed a dirty, smelly route of convenience, rather than the vibrant route of choice for visitors and businessmen in the mid-1800s.

Cross Bienville Street, however, and you can feel a liveliness return to the passage. The colorful signs of restaurants, bars, art galleries, and museums line both sides of what has now become a pedestrian mall. The showroom and workshop for Bevolo Gas & Electric Lights is a reminder of how the street would have been lit at night 150 years ago. The smell of chargrilled oysters and escargot fill the street as you step toward the Pelican Club where white tablecloths and black-tie employees are an additional throwback to the past as are the streetpainters.

In search of a court building

When Exchange Place arrives at Conti Street it appears to have concluded its journey at the Louisiana Supreme Court building. This massive building, however, wasn’t built until 1910.

Before that, Exchange Place traveled one more block.

At the turn of the 20th century, Louisiana needed to expand and modernize its most prestigious court, which had been at the Cabildo in Jackson Square beside St. Louis Cathedral since the 1860s.

When the need to expand was first brought up, the original plan was to replace the historic Cabildo and its adjacent Presbytere with a new, modern court building. Thankfully, public outcry stopped the local treasures from being torn down.

As that plan fell through, a new one emerged. Remember how we said that Exchange Alley traveled between two exchanges? The first was the Merchants’ Exchange, mentioned above. The second, however, was the old St. Louis Exchange Hotel (now the Omni Royal Orleans hotel).

Once plans for replacing the Cabildo fell through, the St. Louis Exchange Hotel became the new target for a potential modern court building. Fortunately again, that plan also failed. Instead, the government decided to build a new courthouse one block upriver of the exchange…directly on top of Exchange Alley’s path where it meets Conti Street.

We can see the court building now, which takes up the entire final block of old Exchange Alley. But, back at the turn of the 20th century, this section of the alley was said to be abuzz with legal and political offices falling into disrepair. A 1906 edition of the periodical, Architectural Art and Allies, reported, “In 1903, when the commission began purchasing or expropriating the properties, the buildings were dark, deteriorated, and tenement-like, and some saw the clearing of this land and the erection of a grand edifice as a means of ‘redeeming a neighborhood.”

Many disagreed, however, seeing it as an attack on the French Quarter’s charm and New Orleans’ remarkable history. In June 1903, as the demolitions were taking place to prepare for the court, the Daily Picayune published an editorial mourning the loss of the square as “one of the most historic sites in New Orleans. It is the very heart of the Vieux Carré … and while still palpitant with memories of the pioneer bravery and colonial splendor, it must be torn to pieces that progress may continue its onward march.”

——————-

With a massive court building in our way, does that mean Exchange Alley has reached its conclusion? Not so fast!

Remember, the alley connected two exchanges, and while we mentioned both Merchants’ Exchange and the St. Louis Exchange, we have really only discussed the former.

In our next article we’ll share the opulent, and also tragic, past of the St. Louis Exchange. We’ll also look at what it must have been like on this incredible street decades and centuries ago.