When you ask most Americans where king cake is eaten, the most frequent answers you’ll hear are Louisiana or New Orleans. But, to the surprise of many, king cake is enjoyed all across Europe and North America.

This is because the king cake tradition began thousands of years ago in Ancient Rome. Mardi Gras (or Christianity, for that matter) weren’t yet a thing, but the Romans were celebrating their biggest annual festival: Saturnalia.

Saturnalia was a multi-day festival, sometimes as long as a week, and it was held during the Winter Solstice in late December. The reason for celebrating was that the longest night of the year was now past and, from here on out, the sun would rise a little higher in the sky each day.

During Saturnalia, Romans ate too much, drank too much, wore colorful costumes, and generally enjoyed debauchery. Sounds familiar, right? At the center of their decadent meals was a cake with a bean hidden inside. Whoever found the bean was crowned queen or king of the Saturnalia. They were treated like royalty and could choose the entertainment for the party. (Early Romans who found the bean, however, were also sacrificed to the gods following the festival, so next time you find the baby and complain about having to buy the next king cake, exercise some perspective!)

As the Roman Republic grew into the Roman Empire, they brought their traditions with them — from the British Isles in the west to Bulgaria in the east–and one of those traditions was their Saturnalia cake.

But this cake took on a new meaning as Rome adopted Christianity. Saturnalia was soon merged into Christmastide, which we now know as the 12 Days of Christmas. The cake with the bean hidden inside found a home on the Twelfth Night of Christmas, when the Three Kings were said to have found the Christ child and gave him their famous gifts.

The name of the cake became Three Kings Cake…and then Kings cake…and then king cake.

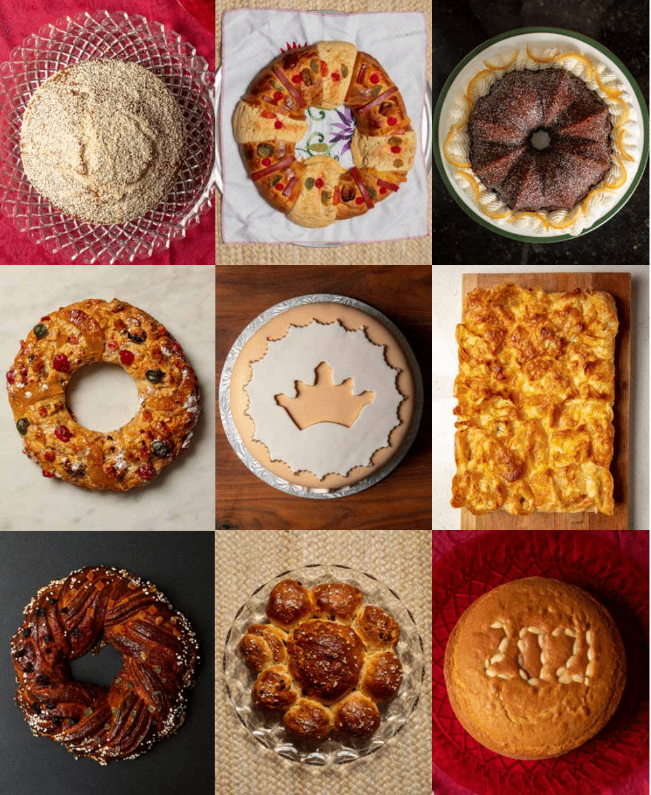

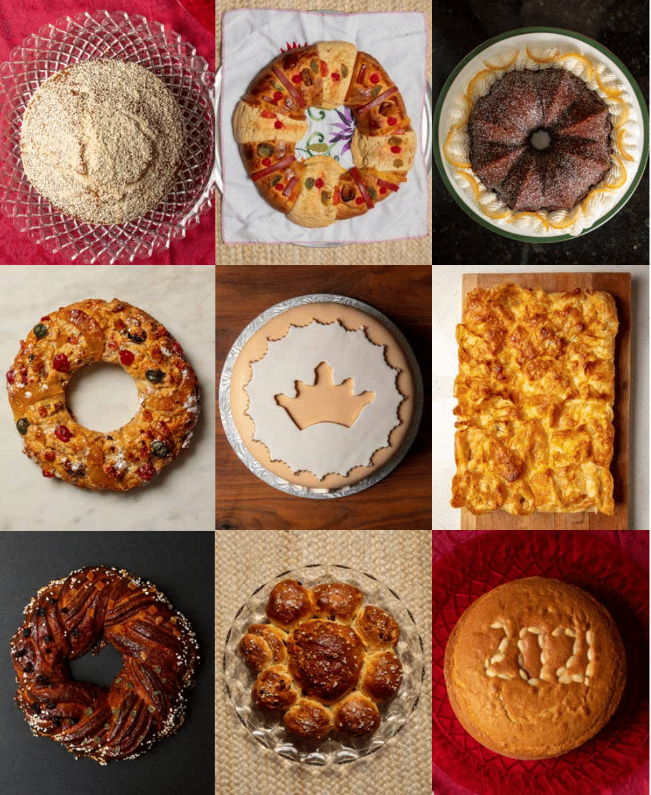

It’s still enjoyed in many countries around the world, particularly in places touched by the Roman Empire or its descendants. The cakes look different, taste different, and their names sound different to us; but the shapes are similar, the times of year we eat them are similar, and those different-sounding names mostly translate to “cake of kings” or “king cake.”

Most importantly, each cake has something hidden inside and whoever finds that hidden something is rewarded with promises of prosperity.

In the entry, below, we’ll look in some detail at the versions of king cakes from France and Spain/Mexico that have most influenced our own Louisiana king cake. Then we’ll do a quick run through a host of other versions—similar to our cake in some ways, but different in many others.

King Cakes in France: Gâteau des Rois and Galette des Rois

Depending on where in France you live, you’ll likely find one of two types of king cake. In northern France, there’s the galette des rois, made of puff pastry and stuffed with a dense, creamy almond frangipane paste. In the south of France, on the other hand, it’s common to find a brioche-style cake, called a gâteau des rois, flavored with cognac or orange blossom. The gâteau has a hole in the center and is covered with candied fruit and granulated sugar—reminiscent of a crown studded with jewels.

The divergent cake styles is the result of a sixteenth century feud between French bakers specializing in breads and French bakers specializing in pastries. Both groups wanted ownership over the lucrative Twelfth Night tradition and created cakes that leaned into their specialties. King Francois I attempted to resolve the dispute, but he failed and a Cake Cold War of sorts continues into modern times.

Whether in a gâteau or a galette, the French have hidden a small ceramic fève inside their king cake for centuries. That fève was typically shaped like a king or a crown. However, after the French Revolution, much of the tradition’s royal imagery was purposely obscured. The cake, which today translates to “cake of kings,” was briefly called the “galette de la liberté,” the “galette de l’égalité,” or even a name that translated to “the Cake of the Men-Without Pants” in honor of the French revolutionaries. Unsurprisingly, those names never stuck. The fève, on the other hand, remains impacted to this day. Rather than a crown, the fève can now be anything: pop culture icons, members of the French World Cup team, or—to recall one memorable set of fèves—each position of the Khama sutra!

The French continue their centuries-old tradition of hiding a small ceramic fève inside a cake to this day. It’s a high stakes affair with everyone desiring that beautiful fève. To avoid accusations of cheating, the youngest child—considered the most innocent—is sent under the table. Unable to see which slice has the fève, or which partygoer is up next, the child assigns slices without bias. Whoever finds the slice with the trinket is crowned queen or king of the party.

King Cakes in Mexico & Spain: Rosca de Reyes

For some families in Mexico and Spain, Twelfth Night (also known as Epiphany) is a more significant part of the Christmas season than Christmas itself! While much of the world looks forward to Santa Claus traveling the globe on December 25, Mexican and Spanish families wait for the biblical Three Kings to bring gifts on January 6, just as they did for the Christ child.

The 12 Days of Christmas is marked by elaborate feasts throughout much of the Spanish-speaking world. While the menu might look different from country to country and family to family, a cake is always served on January 6. In the Catalonia region of Spain that cake is called the tortell de reis, in the rest of the country it’s the roscón de reyes, and in Mexico they call it a rosca de reyes. But in each instance, the translation is the same: cake of kings.

Although there are variations in each version, all the cakes are made from a brioche-like dough, similar to what you’d find in southern France and in Louisiana king cakes until the 1970s. The dough is flavored with orange blossom water or rum and adorned with candied fruit such as cherries, orange, quince, and figs to resemble a jeweled crown. Fillings can vary from the sweet, whipped cream most popular in Spanish cakes, to less traditional options like chocolate, strawberry, or marzipan. The Mexican rosca de reyes typically has no filling, but stripes of sugar paste join the candied fruit topping.

What’s hidden inside the cake also varies. In Spain, the roscón de reyes includes a bean, as well as either a tiny figurine of a king, the baby Jesus, or a figure from pop culture. The partygoer who finds the bean is expected to buy the cake next Twelfth Night while the attendee who finds the figurine wears a paper crown as a symbol of their Excellency.

In Mexico, only a baby figurine is hidden inside the cake, symbolic of how Mary and Joseph hid their baby from the persecution of the Roman-backed King Herod of Judea. The partygoer who finds the figurine is expected to host a tamale party on the Día de la Candelaria—another important date on the Catholic calendar and related to our Groundhog’s Day.

King cakes across Europe

Many of the early European inhabitants in New Orleans were from southern France and Spain, which explains why our king cakes have the most similarities to theirs. But even after the king cake arrived in Louisiana, it would take hundreds of years for it to evolve into the unique purple, green, and gold custom we love today.

But, while southern France and Spain are the closest ancestors to our king cake, there are many other varieties around Europe.

Switzerland and southern Germany, for example, have dreikönigskuchen. It’s a fluffy, brioche-like cake made of separate rolls arranged in the shape of a crown and sometimes adorned with rum-soaked raisins or chocolate chips.

For centuries in England, one could find breathtaking fruit cakes baked with brandy, covered in a layer of beautiful royal icing, and topped with elaborate, expensive sugar figurines and etchings. Today, the tradition lives on as a fruit cake-like Christmas pudding with a coin hidden inside. During preparation, each member of the family is told to make a wish and stir the mix three times. If an unmarried person doesn’t take part, legend says they won’t find a partner in the upcoming year. (Ouch!)

The banitsa is common during the Christmas season in Bulgaria—featuring a dogwood branch and/or a series of fortunes for partygoers to find. Greece and Cyprus enjoy a vasilopita on New Year’s Day with the year often etched on top of the cake and a hidden coin baked inside. Whoever finds the coin is awarded a prize. At office parties that sometimes means bonuses that would put even the Three Kings’ gifts to shame.

In Portugal, the bolo-rei has two items hidden inside: a charm and a bean. Whoever found the charm is said to have a year of good luck ahead of them. Whoever finds the bean, however, has to buy the next cake. Like those Louisianans (you might be one) who are unhappy to find they are responsible to buy the next cake, the Portuguese also see finding the bean as bad luck. They are known to exclaim, “Calhou-me a fava!” which means, “I got the short end of the stick!” or even “vai à fava!” which translates to something far too rude to publish here!

So next time you’re eating a slice of king cake (hopefully today!), remember this isn’t only a tradition shared by the residents of Louisiana. People across half the world are enjoying their own version of the cake of kings, as well.