Include a Topper!

-

Happy Birthday Banner

$9.00 -

Jack-o’-Lantern Cake Topper

$10.00

Add Ons

Your cart is currently empty!

Since 1949 celebrating 75 years. Order online or call us at 1 800 GAMBINO (426-2466)

Speakeasies are all the rage these days. New Orleans has one downtown, below the Orpheum Theater, called “Double Dealer.”

It’s a throwback to the 1920s, when shady characters with memorable nicknames (think national figures such as “Scarface,” “Lucky Lucciano,” and “Ice Pick Willie”) illegally provided Prohibition-weary New Orleanians with the booze they so badly wanted.

In modern times, these recreations of secret underground bars, attract upstanding patrons looking for something fun and unique.

A century ago, however, speakeasies drew a more notorious crowd. One whose collective name started with an “m” and ended with an “afia.”

“The mafia in New Orleans?!” you might be wondering. “That was more of a New York and Chicago thing, right?”

Wrong.

Not only was New Orleans a center of America’s network of mafia families… many historians believe New Orleans was the original center.

If you promise not to tell any “Made Men,” we have a very interesting story to tell you. We’ll begin with Part 1 here, and then follow-up with Part 2 soon. This is the story of the New Orleans mafia.

From Sicily to New Orleans

For much of the 19th century, Italy wasn’t the unified nation we know today.

Earlier that century the Mediterranean island of Sicily was merged into a kingdom with Naples. This merger was against the will of the Sicilians who wanted their independence. Their dream was briefly achieved in 1848 when they revolted and won, but Naples took back control the following year and enacted oppressive policies toward the rebel island. Those policies—combined with a local economy that struggled to compete in a unified Italy—triggered a half-century-long diaspora of Sicilians across the Atlantic Ocean.

No city in America received more Sicilians during that exodus than New Orleans. Between 1884 and 1924 an estimated 290,000 Italian immigrants—many from Sicily—arrived here.

But why choose New Orleans?

The conclusion of the American Civil War allowed freed former slaves the choice between staying in rural areas to work the fields, or heading to cities for higher-paying jobs. Not surprisingly, many chose to leave for the cities.

The Louisiana Bureau of Immigration was formed to recruit new agricultural workers. They had success attracting Sicilians, offering them the opportunity to move beyond their previous lives of mere subsistence farming.

Raffaele Agnello, a Sicilian, arrived in New Orleans by about 1860, earlier than the wave of his countrymen that would begin two decades later. He was from Palermo (located in northwestern Sicily) and was already a mafioso before leaving his homeland.

In New Orleans, when Confederate forces and local police abandoned the city during the Civil War, Agnello was a leader in the European Brigade—a group of immigrants tasked by the mayor to keep order in the city. His position in the brigade helped him consolidate local Italian power into the Crescent City’s first mafia, earning him the nickname Zu (or Uncle).

Agnello and his brother, Joseph “Peppino,” gained strength as more Sicilians from Palermo flooded the city. They controlled the Italian dockworkers and skimmed money from the fruit trade those workers handled.

This attracted the attention of Joseph “J.P.” Macheca, a man born and raised in the Italian-American community of New Orleans and heavily involved in the importing of fruit.

Macheca organized and funded The Innocenti, a politically motivated group that gained support from New Orleanians with ties to the eastern side of Sicily. The Innocenti set up guards and patrols around the French Quarter—called Little Palermo—and that felt like a threat to Agnello, triggering America’s first Mafia War.

It was a bloody and complicated affair, involving political officials, set-ups and a whole lot of “whacks,” but we don’t have time for all that here. Suffice it to say that on the morning of April 1, 1869, Raffaele Agnello, the first Godfather of New Orleans, walked by the French Market and through the Quarter with his bodyguard, greeting his supporters. The two turned the corner from Old Levee Street (now Decatur Street) onto Toulouse Street, just outside the J. Macheca & Company fruit store. The bodyguard was distracted by a sound behind them, and in that instant Agnello was shot in the face and killed.

Agnello’s brother, Joseph, was killed a few years later, leaving New Orleans’ organized crime network to Macheca.

The Black Hand

Macheca and his group fell under a mafia splinter organization based in Monreale, Sicily, called the Stuppagghieri. Beginning in the 1870s, they established lucrative organized criminal activities such as extortion (with noncompliant businesses set aflame), labor racketeering and—like their Agnello-led predecessors—collecting tribute payments from Italian laborers and dockworkers. They also collected payments from the powerful, rival Provenzano crime family… at least for a while.

By the early 1880s, Joe Provenzano was dominating operations on the docks, and decided to split from Macheca’s Stuppagghieri. For the next six years, the two sides imported hundreds of Sicilian criminals to bolster their strength—with the Provenzano group pulling from the Palermo Mafia that once supported Agnello, and Macheca being supported by the Stuppagghieri.

War between the two sides broke out in 1888.

For decades the city’s non-Italian residents were growing increasingly angry with their new neighbors. As far back as 1869, the New Orleans Times wrote how parts of the city were overrun with “well-known and notorious Sicilian murderers, counterfeiters, and burglars, who—in the last month—have formed a sort of general co-partnership or stock company for the plunder and disturbance of the city.”

Cleaning up the streets was tasked to David Hennessy, 29 years old and just recently appointed to be New Orleans’ police chief. Hennessy had a history of fighting organized crime, capturing the notorious Giuseppe “Vincenzo Rebello” Esposito, wanted in Italy for—among other things— kidnapping a British tourist and cutting off his ear.

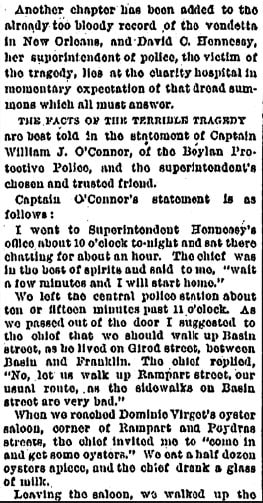

Hennessy made progress mediating the war between the two factions, but on the night of Oct. 15, 1890, he was shot by several sawed-off-shotgun-wielding gunmen on his way home beside where the Hyatt Regency Hotel on Loyola Avenue is today. Hennessy died the next day, but was said to have blamed the “Dagos” — a derogatory term for Italians. (In the article excerpt, below, written hours after the shooting, I love how it was noted that the fallen chief’s last meal was a half-dozen oysters and “a glass of milk.” Only Hennessy and only in New Orleans.)

Hysteria swept over the city and as many as 250 Italians were rounded up for questioning. Nineteen men were ultimately charged with the murder—or as accessories to the murder—and were held without bail in the parish prison just upriver of where the Mahalia Jackson Theater now stands. One of those men was Joseph Macheca.

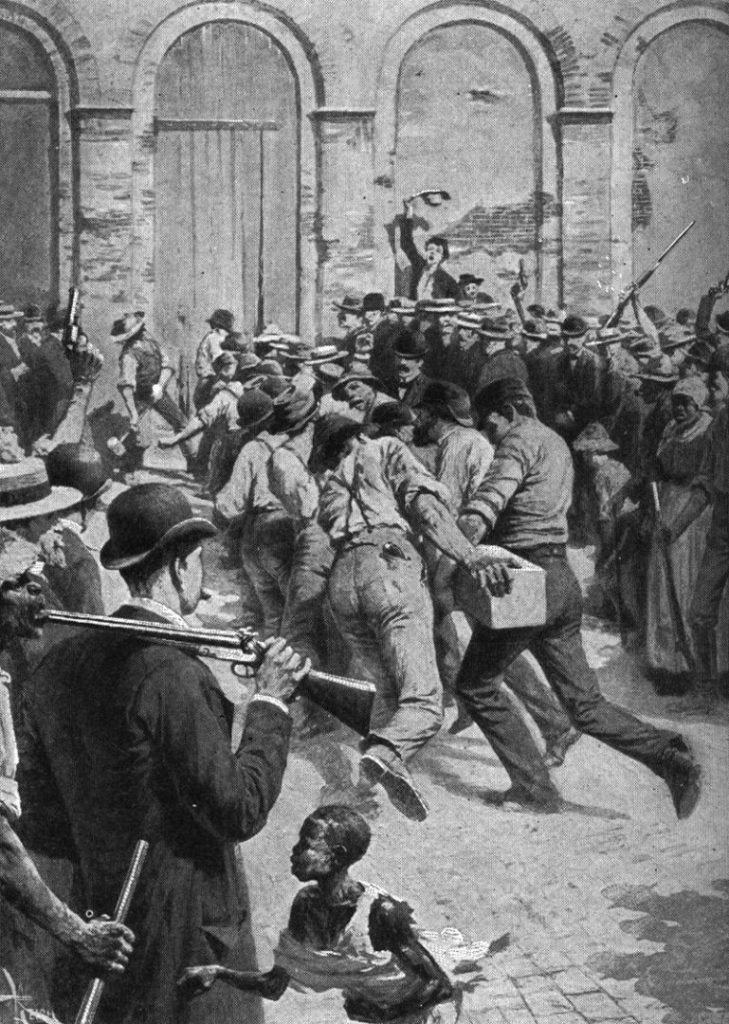

When none of the accused men were found guilty, tensions overflowed. An angry mob of thousands of non-Italian New Orleanians stormed the prison. Eleven of those 19 men were lynched or shot, while the others managed to hide.

Many believe this to be the largest single mass lynching in U.S. history.

It’s a tragic way to end the first of our two entries about the history of the New Orleans’ mafia, but surely you didn’t think an article about organized crime was going to be all kittens and roses.

In our next post, we’ll cover how these early decades led to the more modern New Orleans mafia of the 20th and 21st centuries. That will include, among other things, a bitter feud between local mafioso leadership and the Kennedy family. Stay tuned!